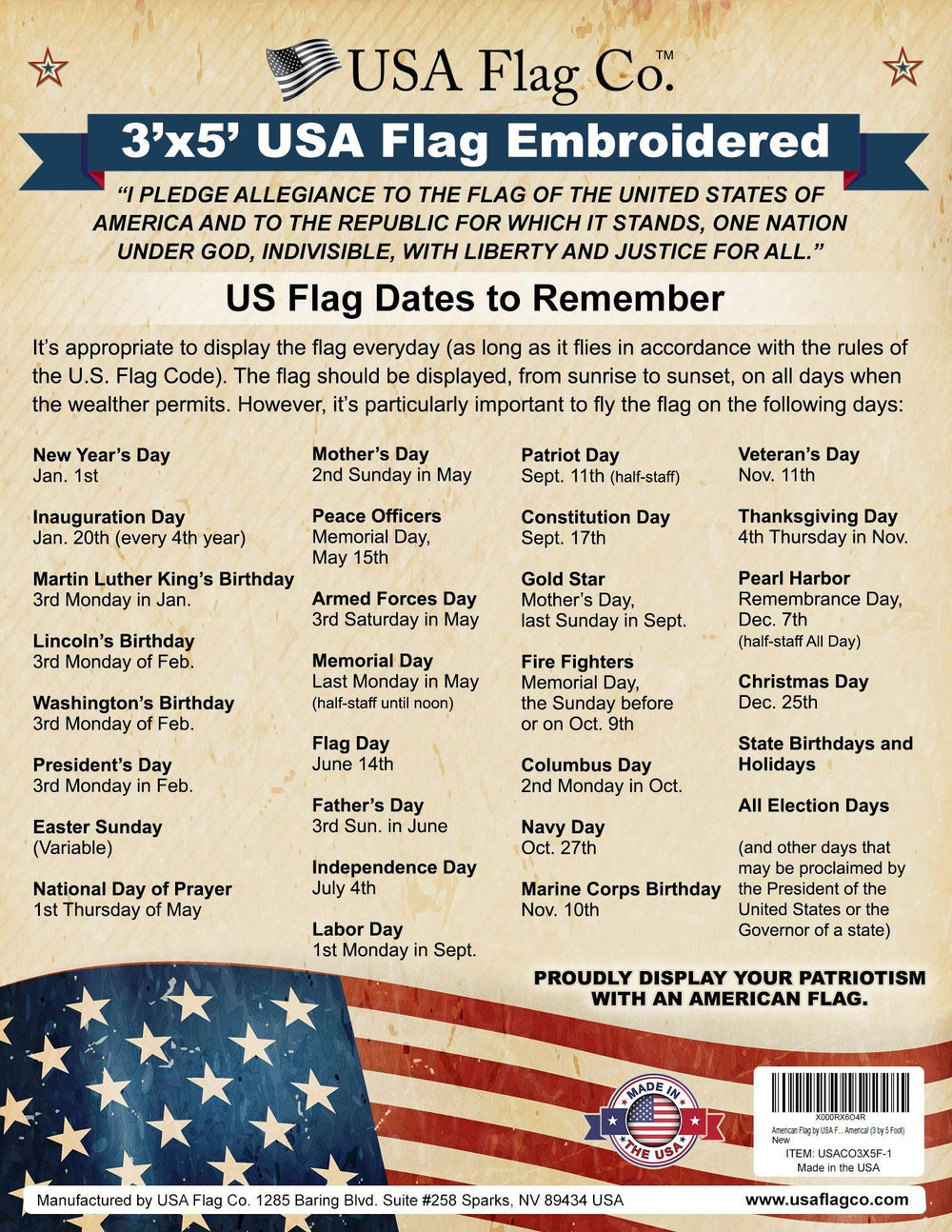

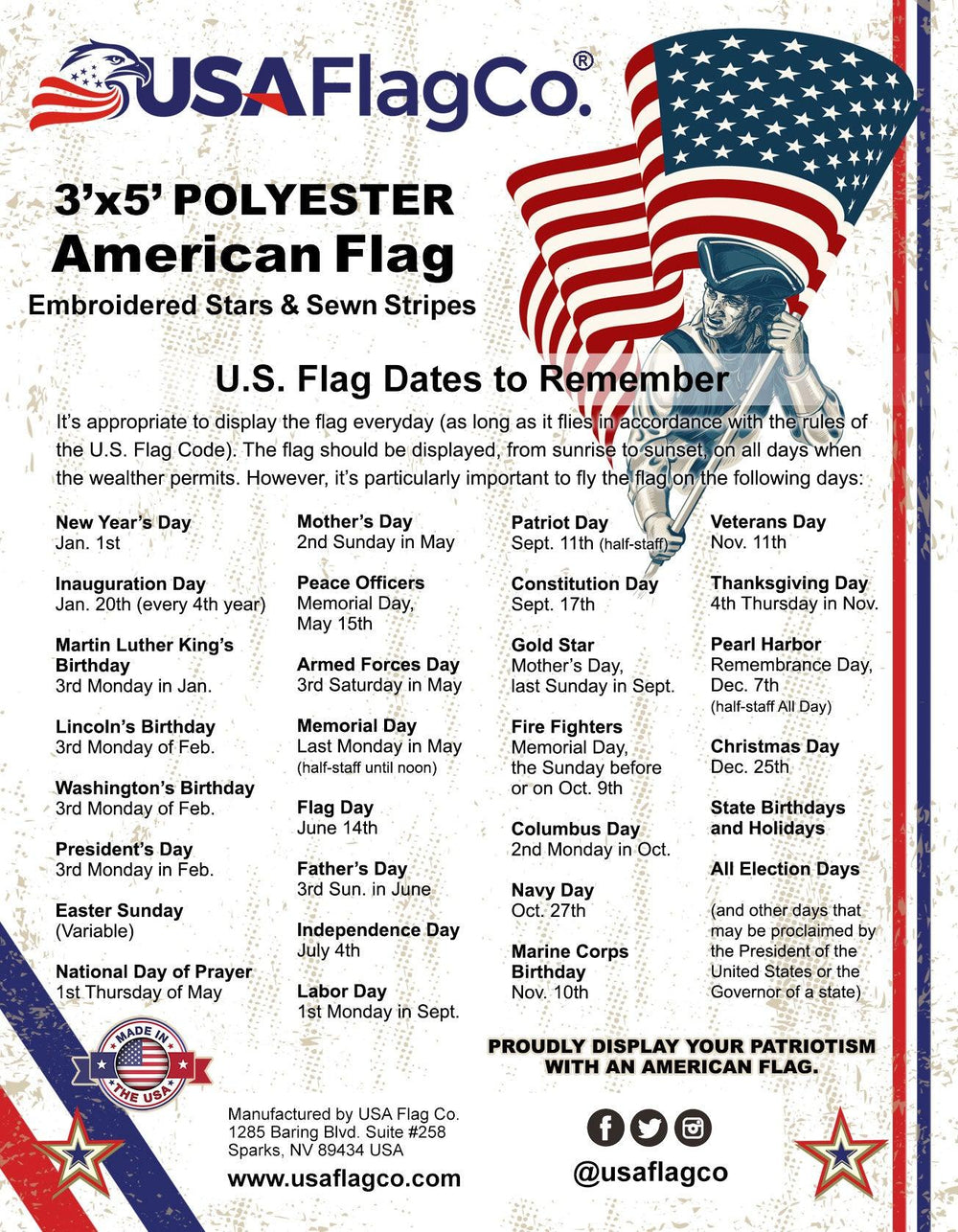

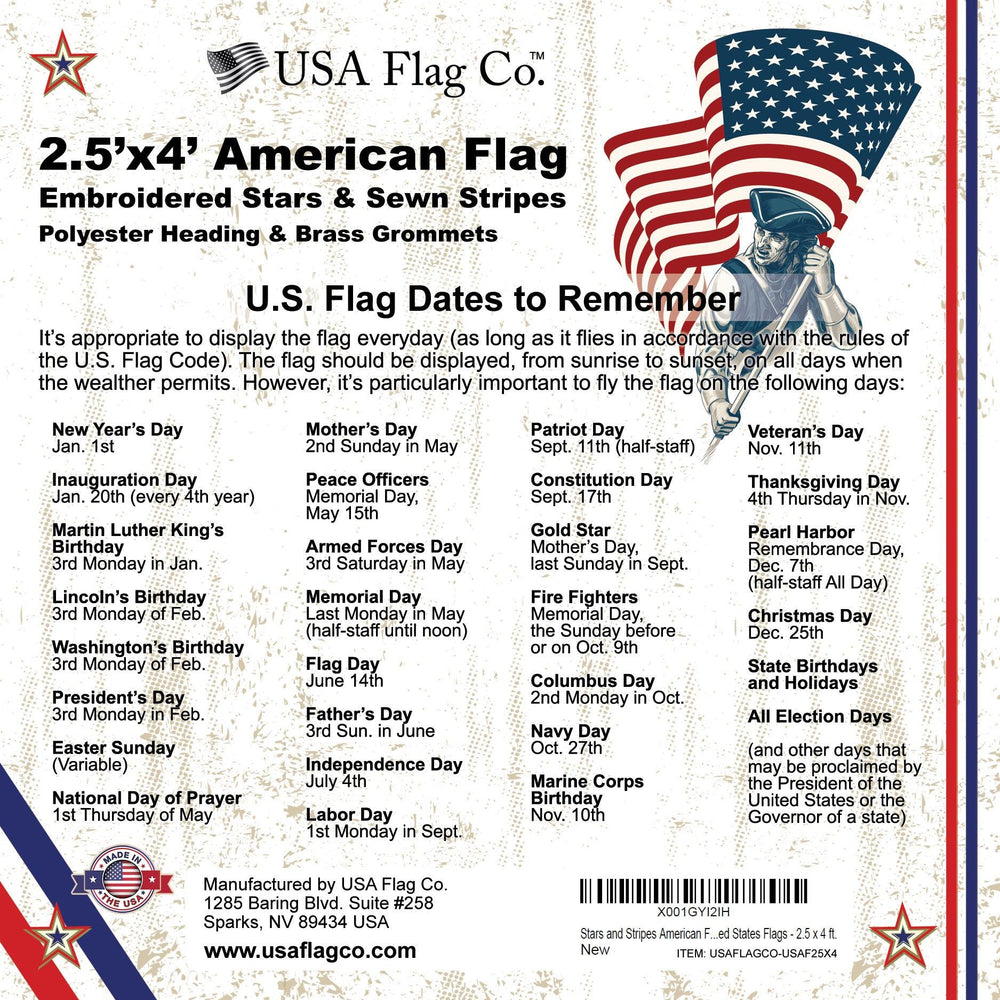

Highlights

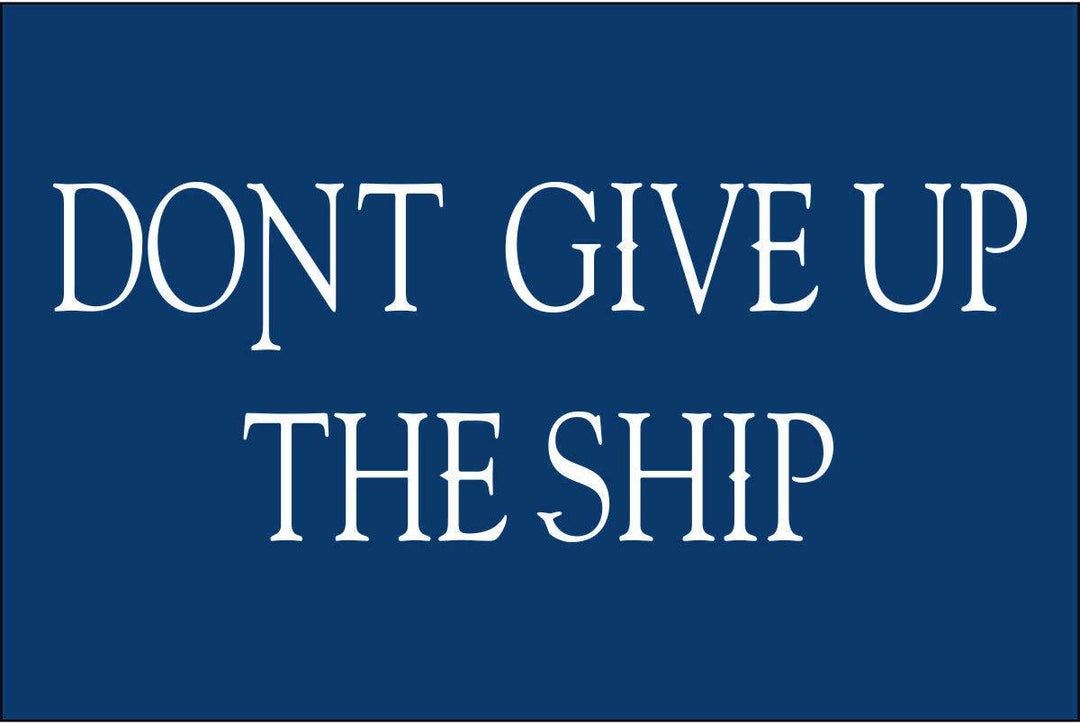

Dont Give Up The Ship Flag

Flag Names: Commodore Perry Flag and Dont Give Up The Ship Flag.

Adopted: June 1, 1813

Dont Give Up The Ship Flag Design: This battle flag was of blue silk, about nine feet square. Across the center, two lines of white letters, about a foot in height, blazoned the immortal words of Lawrence, DONT GIVE UP THE SHIP.

Dont Give Up The Ship Flag History

The Battle Flag Is Hoisted

The evening of September 9th was a beautiful summer night, with a full moon shining peacefully on the quiet waters of Lake Erie, as the squadron lay at anchor in Put-in-Bay. Onshore were seen the white tents and campfires of a battalion of infantry, sent over by General Harrison to guard the stores of the fleet, and as additional protection against a night attack on the vessels.

The second lieutenant, Dulaney Forrest, came on deck at five bells, carrying a signal flag, and called Patterson to fly it at the fore-top of the mainmast. Fluttering in the light breeze it called every commander in the fleet to come aboard the flagship.

Harry Macy was walking about among the guns of the first division. The men of the crew were seated on the guns, or on the combing of the folk's, or standing about the capstan. Two of the Kentuckians, who had asked him many questions, now came up to inquire what the signal was.

"It is to call the commanders to a conference with Captain Perry. Come up on this gun, and you can see the boats come over."

It was a pretty sight as the white boats darted towards the Lawrence, the oars flashing in the moonlight as they lifted and swept forward and back together. Lieutenant Yarnall stood at the port gangway and received each officer, and either he or Lieutenant Forrest accompanied them to the cabin. The careful etiquette displayed in their reception, and the splendid uniforms, made a great impression on the western men, and one of them remarked,

"It must be a good deal like the President’s reception.”

The talk ceased while the officers were coming aboard, but began again when they went below; for this was the social hour, when the men were free to go about on the foredeck. The officers of the ship were on the quarter deck in groups, from which came bursts of easy laughter. The groups were apt to form around the jovial, handsome lieutenant of marines; for Brooks was full of life and spirit, and a favorite among officers and men. Harry looked over there with longing eyes. He would like to be among them and felt that he was better entitled to a place there than some of the young midshipmen, who knew far less than he did about sailing or fighting a vessel. He wondered if he might be promoted to a midshipman’s berth if he should do his part well in the coming battle.

In 1865, artist William Henry Powell painted Perry's Victory on Lake Erie, which now hangs in the Ohio Statehouse. Eight years later, he created this larger version in a temporary studio in the U.S. Capitol. The work depicts the moment when Perry made his way from the Lawrence to the Niagara. Powell used actual sailors as models for the unknown oarsmen and noted the diversity of Perry's crew by including an African-American, seated toward the right. The frame features Perry's message to General Harrison in gold lettering at the top and the name and date of the battle on the cartouche at the bottom.

In the meantime, important matters were being discussed in the cabin. Captain Perry made a statement about the character and strength of the vessels in the enemy’s fleet. He outlined his plan of attack, and what should be done to overcome their superiority in the length of the range. He reserved for Lawrence the hardest and most dangerous task, to attack the Detroit, and assigned the duty of meeting Queen Charlotte to Captain Elliott with the Niagara. He went on to speak of his pleasure in having Captain Elliott as his second officer. The commander then gave each one his written instructions for their action in the battle, the name of the enemy’s vessel they were to attack, their position in the line, and every detail necessary for their conduct. He also gave them a little talk about the contingencies which might arise, and his wishes for their conduct under these conditions.

Mural began by Charles Robert Patterson and was completed in 1959 by Howard B. French. It depicts the U.S. Brig Niagara, the flagship of Master Commandant Oliver Hazard Perry, raking the British warships Queen Charlotte and Detroit, which are afoul of each other after colliding. Niagara is flying Perry's "Don't Give Up the Ship Flag" at her mainmast peak.

Captain Perry then sent for the purser, Mr. Hambleton, and asked him to bring in the burgee which he had made for the flagship. This battle flag was of blue silk, about nine feet square. Across the center, two lines of white letters, about a foot in height, blazoned the immortal words of Lawrence,

DONT GIVE UP

THE SHIP

“The hoisting of this flag will be the signal for going into action,” he said.

The commanders examined the flag with interest and heard the purser tell how it was made by the young women at Erie. Then Captain Perry gave his closing

instructions:

"I intend from the beginning to bring the enemy into close action with the utmost rapidity, in order to overcome his advantage in long guns and to make the best use of our heavy carronades. I will end this conference by reminding you all of Lord Nelson’s weighty charge to his officers:

"If you lay your enemy close alongside, you cannot be out of your place."

Soon after this the officers retired to their vessels, and quietly settled on the fleet, and when the men swung themselves into their hammocks they dropped asleep, although they knew the morning might usher in a bloody battle.

Second Lieutenant Dulaney Forrest was the officer of the deck in the morning watch, and soon after dawn the lookout at the masthead of the Lawrence shouted,

"Sail ho!"

"Where away?" called the lieutenant.

"Nor’west by Nor’, Sir."

The lieutenant immediately went below and called Captain Perry, and in a few moments, he was on deck, just as the peak of another vessel lifted above the horizon.

"Lieutenant set the signal,

"Underway to get,"

"and have all hands called to quarters.""Bosun, call the men to quarters,"

Lieutenant Forrest called, as he hurried away to get the signal flag. A few minutes later everyone but the sick was in his station, and all eyes were turned to the northwest, where, one by one, the enemy’s vessels now appeared until six were counted.

Then came orders sharp and quick, to weigh anchor, and send the topmen aloft to unfurl the sails. The breeze, however, was very light, and the boats were lowered and cables paid out to tow the laggard fleet out into the open lake, and the gunboats got out their sweeps to help get underway. The passage was a narrow one, and the wind from the southwest forced them to make frequent tacks. Westward lay Rattlesnake Island and north of it Middle Bass, the direct passage to Detroit river lying between these two islands.

Barclay’s fleet came steadily on towards the group of islands, and it appeared that he was not trying to slip by, but seeking a battle. This movement showed his confidence in the ability of his fleet to meet the Americans. As the sun rose higher, and their course could be determined, Perry said to his officers,

"Barclay intends to fight. He thinks he can beat us, and in some respects, his fleet has superiority over ours. But I have a strong faith that this day we will destroy them, or compel them to surrender. Our men have been well trained and drilled; and the recent naval fights have shown, that with anything like equal equipment, the Americans have always won."

"We all believe it,” Lieutenant Forrest replied,

"The men, who can get on deck, are eager to show their valor, and the sick ones are cursing their fate that they can not do their part."

"How many are on the sick list this morning?"

"Thirty-four."

"That leaves us one hundred and three effective men."

Harry was anxiously watching for a change in the wind, which was still very light and from the southwest. He knew that Captain Perry would want to have the weather gage of the enemy, in order to sail in upon them with the utmost speed, before their long guns could cripple the fleet. But Barclay’s fleet was in such a position that this was impossible if Perry took the shortest way out of the channel of the islands. Perry would be obliged to beat around Snake Island. The light wind gave them little headway, and time was passing. The commander was walking about impatiently, and discussing the matter with Sailing-master Taylor. Perry began to fear that Barclay might escape to Long Point after all, for it was past nine o’clock, and they were still in the lee of Snake Island.

"We must wear ship and run to the leeward of the islands," he said to Mr. Taylor.

"If you do, Barclay will force you to fight him to the leeward."

"I don’t care. To windward or to leeward, they shall fight this day."

Mr. Taylor then gave the necessary orders to run before the wind, but hardly had the sails been changed and the yards braced when the wind changed to the southeast. New orders were at once given to the men on the yards, and other men sent aloft, and soon the whole squadron with all sails set was steadily moving out on the windward of Snake Island.

As Harry came down the ratlines the sergeant of the Kentuckians beckoned to him, and he went to him.

"Say, mate, what does all this change of sails mean? We’uns don’t understand it."

"Captain Perry wants to keep the weather gage of the enemy."

"That’s worse than Shawnee jabber to we’uns."

"Well, I’ll try to explain," Harry said with a laugh, "If we keep on the windward side of the enemy, we can sail up to him more rapidly than if we were on the lee, that side," pointing to the northeast.

"Their long guns will shoot farther than these heavy guns. We want to get close as soon as possible, so our heavy guns will break them up."

"And if we had to come upon the lee, what then?"

"They would have the wind in their favor, but would have to come up bows on, and could not fire a broadside. And we could use our broadsides."

"Then I hope we will have the wind on them and can rush the fight as fast as Perry can crowd on the sail."

"Well, that is what we want. But whatever our luck is in the wind, our commander will force the fighting. He knows what to do in all the conditions of wind and water."

While they were beating around the island Perry, after frequent examinations of Barclay’s fleet with his glass, was satisfied that their line was not arranged as he had supposed it would be. He had expected that Queen Charlotte would be in the lead and had placed the Niagara in the van to meet her. So he signaled the Niagara to heave to and talked with Captain Brevoort, who knew all of the enemy’s vessels except the Detroit. Brevoort informed Captain Perry that the schooner Chippewa was in the lead, the Detroit second as all could see; then the brig Hunter; then the Queen; the schooner, Lady Provost, and the sloop, Little Belt.

Perry then changed his line to meet this arrangement. The Lawrence in the van, with the Scorpion and Ariel on the weather bow to engage the Chippewa and the flagship; the Caledonia to follow the Lawrence to meet the Hunter; the Niagara to engage Queen Charlotte; the Somers, Porcupine, Tigress, and Trippe to take care of the Lady Provost and Little Belt, as they came on the enemy’s extreme left.

It was after ten o’clock when the fleet cleared Rattlesnake Island, and, with a three-knot breeze from the southeast, formed in line, and sailed on toward the enemy, distant six or eight miles nearly north. The English fleet was lying hove to on the port tack, their bows to the westward, and as all of them had just been painted they looked like a flock of beautiful canvas back ducks to the tall Kentucky sergeant, who had been so friendly with Harry Macy.

"We have no cover now. Won’t the pesky birds fly up before we git dost enough to wing 'em?"

"I don’t understand you," Harry answered.

"I can’t git it outen my head that we are running on a flock of ducks or geese, and they will fly up before we git a line on 'em."

"They will do more than quack or hiss when you tackle them. No danger of their flying away now. They are waiting and will give us a shower of iron hail

before we get in range."

Lawrence was cleared for action. The bo’sun piped the topmen below, and all were sent down to bring up their hammocks. These were placed in casings on the top of the bulwarks, as protection to the men from the fire of marines on the tops of the enemy's vessels. The shot was laid in the racks or piled up in grummets of rope. Boys were running to the magazine for cartridges, which they carried in covered buckets. Squads of men were sent below to bring up the boarding weapons, pikes, cutlasses, and pistols. These were stacked up at the foot of the masts. Buckets of water were dashed over the decks and sand was sprinkled on them. Why this was done was a mystery to the landsmen, but all were too busy for explanations.

Harry Macy was sent aloft to examine all the rigging and sails, blocks, yards, stays, and braces, and reported all in perfect order. Then Lieutenant Yarnall ordered the boatswain to get out preventer braces and reeve them fore and aft, and for a while, the topmen were busy running these in the blocks and binding together the upper masts and sails, which would soon be cut and torn by the iron hail.

The commander now came forward, followed by his brother Alexander, carrying the blue silk battle flag. Stepping up on a gun slide, he called the men all around him, and taking the flag, shook out its glistening folds until the motto could be seen by all.

"My brave lads! This flag contains the last words of Captain Lawrence, 'Don't give up the ship.' It is my charge, as we go into battle. Shall I hoist it?"

'Ay! Ay! Sir!' every seaman answered, and the marines joined in with a hearty response. Then Midshipman Perry fastened the flag to the line, and Lieutenant Yarnall hauled it up to the main royal masthead.

Every vessel saw the signal, and as the folds were shaken out by the breeze and the men below gave three hearty cheers, the men on the other vessels repeated the cheers.

"Let the men have their noonday drink, and bring out the bread bags," the commander said to Yarnall.

Then he passed all around the deck, examining the guns in turn. These were all upon the spar deck, for the vessels were too shallow to permit a gun deck below. The men were partly protected by the bulwarks on the brigs, but the schooners and sloops were without these, and the men fought without any cover. The gun crews opened the ports and drew the guns to and fro in their slides to show that all were in perfect order.

In the first division were some men from the Constitution. These old fighters saw that the day was going to be a hot one, and had stripped off all unnecessary clothes. Most of them wore only shirts and trousers and had wrapped a bandanna around their heads, and a few men took off their shirts.

"Well boys, are you all ready?"

"Ay Sir. Already, Captain !" they answered, touching their foreheads.

"I need not say anything to you. You know how to beat those fellows."

Next, he came to the gun where Tom Starbuck was in charge, for the gun captain was sick. And beyond it on the next gun were other men whom he had trained on Long Island Sound. His dark eyes kindled as he saw them fully prepared and eager to do the courageous work, for which he had trained them.

"Here are my Newport boys! They will do their duty I warrant."

"We are ready, Sir," Tom replied. "I wish the rest of our shipmates were here."

"You utter my own wish, Tom," Captain Perry answered, and over his face there passed an unmistakable shade of regret, as he thought of the injustice of taking his men away from him when he needed them so much. Then with a smile, he turned to Tom.

"How glad I am to see you here, sober, healthy, strong, a fine young seaman, ready to defend your country’s honor."

"I owe it all to you, Sir," Tom replied in a low voice.

Captain Perry gave him another look, in which there passed from the one to the other the recognition of strong, mutual regard. Then he went on his rounds about the ship, with a few words to each crew, which knit to him the heart of every man on deck, and roused the enthusiasm of all to do their duty at all hazards that day.

Now came more than an hour of silent waiting, as the fleet slowly approached the enemy under a light breeze of three knots. The men were closely stationed at quarters. None but the topmen and sailors at the ropes were allowed to move, and no talking was permitted. The only sounds were the creaking of the blocks, the flapping of the canvas, or the bosun’s whistle, and the sharp orders of Lieutenant Yarnall.

The commander went below and looked over his papers. His official papers, signals, etc. were wrapped up, and heavy lead plates tied about them. He called purser Hambleton, and said to him,

"If I should be killed, and the vessel falls into the hands of the enemy cast these overboard at once."

He tore up his wife’s letters and threw them out of a porthole.

"Our lives are in God’s hands. My wife is praying for me. The enemy shall not read her sacred messages."

In a moment he added,

"This is the most important day of my life. I pray God He may give us the victory."

Many and serious were the thoughts of the men as the fleet slowly crept on into battle. Up in the tops were some of the best Kentucky sharpshooters. And now the most inspiring sight was seen, as one by one the sick men who could walk came slowly up the gangway, and asked that they might be allowed to have their part in the battle. The sun was mounting to the zenith, and they knew they would soon be in the range of the long guns of the Detroit. Harry at his post was crowding on all sail, but his thoughts went out to his mother and to Ruth, and then in a wordless prayer that he might not flinch in the conflict, but be able to achieve something for his country.

Read the whole book below:

"DON'T GIVE UP THE SHIP" by Charles S. Wood - 1912 (PDF) Available online – 137 MB

NOT ALL DONT GIVE UP THE SHIP FLAGS ARE THE SAME!

HERE'S WHY...

Extra care is taken in making these flags. Flag designs are researched to ensure that they are authentic and current. We use sturdy fabrics, allowing the flags to be flown outdoors, indoors, or carried in parades.

Constructed with 100% Heavy Duty Nylon (digital dyed) ★ Beautiful, brilliant colors ★ Resistant to wear and tear of sun & rain ★ Complete with heavy canvas heading & brass grommets to meet the most demanding commercial and residential uses.

- All outdoor flags are finished with heavy-duty thread, polyester heading, brass grommets, and four needle fly hem

- State flags constructed to precise specifications

- Flies in the slightest breeze

- Proudly Made in the USA

- Beautiful Presentation - This Dont Give Up The Ship Flag makes an excellent gift for friends, parents or to PROUDLY display on your HOME or OFFICE.

HEAVY-DUTY NYLON OUTDOOR FLAGS WITH SOLAR SHIELD

Our most popular and versatile outdoor Dont Give Up The Ship Flag, USA Flag Co. flags offer the optimum combination of elegance and durability for every purpose. The 100% nylon material provides a rich, lustrous appearance. Our flags have superb wearing strength due to the material’s superior strength-to-weight ratio and will fly in the slightest breeze. Our historic flags are finished with strong, polyester canvas headings and spurred brass grommets, and four needle fly hem. The result is a flag that will be flown with pride year after year.

SOLAR SHIELD

- Rich, Vivid Colors

- Durable

- Fire-Resistant

- Mothproof

- Mildew Resistant

- Sheds Water

- Lightweight for Flyability

Add this Dont Give Up The Ship Flag to your cart for Immediate Delivery Now.

30-DAY MONEY BACK GUARANTEE

USA Flag Co. wants you to be completely and perfectly satisfied, and that is why we offer a 30-day money back guarantee from the date you ordered your product(s). Now don't get me wrong, we'd love to know why you didn't like it, but only if you are willing to tell us. Otherwise, it's 100% satisfaction guaranteed return. No questions asked.

We take all the risk out of ordering by offering an unmatched satisfaction guarantee. We'll always do our best to take care of you.

100% SATISFACTION GUARANTEE!

Free standard shipping on orders over $60. Full shipping policy

This product is eligible for returns. Full returns policy

Frequently Asked Questions

This is the most common question asked in the industry and the most difficult to answer. No two flags will wear the same due to weather conditions and how often the flag is flown. Our flags offer the best stitching and highest quality materials to get your flag off to a great start.

Do not hang a flag where the wind will whip it against rough surface, such as tree branches, wires or cables or the outside of your home or building. Inspect your flags regularly for signs of wear. Repair any minor rips or tears right away this can be mended easily with a sewing machine or sewing kit. Keep the surface of the pole free of dirt, rust or corrosion that could damage or stain your flag.

We recommend that you hand-wash your flag with mild soap, rinse thoroughly and air dry. You can also use a dry cleaning service.

Exposing your flag to rain, wind, snow or high winds will shorten the life of your flag considerably. If you leave your flag exposed to the elements, it will greatly reduce the life of your flag.

Yes, as long as your pole is large enough to support the weight of the flags. The USA Flag must always fly at the top. The flag underneath should be at least one foot lower and be one size smaller than the USA Flag. Flags of other countries are not to be flown beneath the USA Flag.

If your flag is significantly faded, torn or tattered it is time to retire your flag. Your flag should be retired privately in a dignified manner. In addition, many local community organizations have flag disposal centers that will dispose of your flag for you.