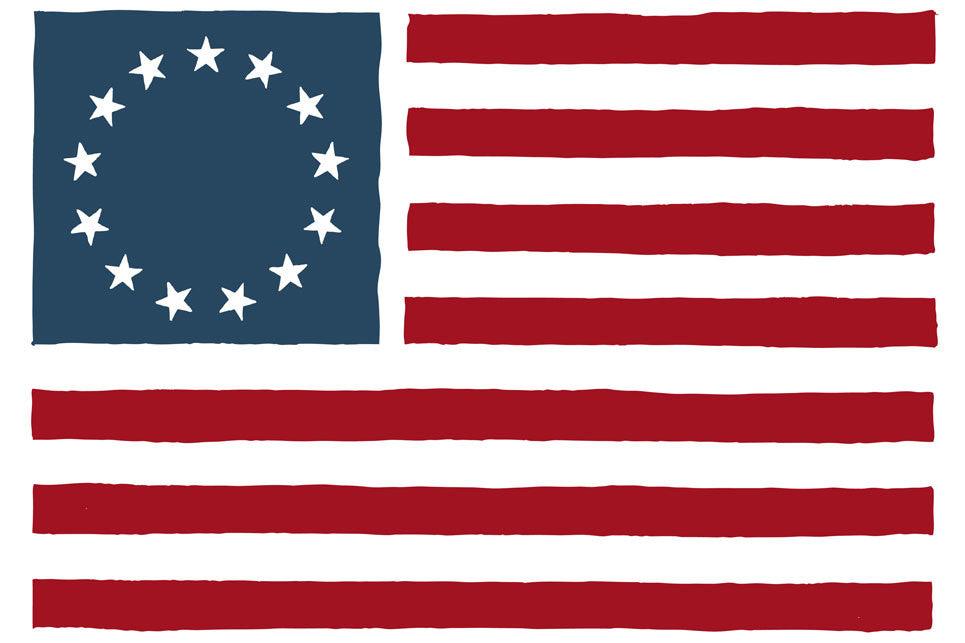

Betsy Ross Flag (1776): History of America's First Flag

The Betsy Ross Story: History of the First American Flag and the Five-Pointed Star

The history of the Betsy Ross flag, and the patriotism of Mrs. Betsy Ross, the immortal heroine who originated the first flag of the United States.

The history of our flag from its inception—in fact, its inception itself—has been a source of much argument and great diversity of opinion. Many theories and mystifications have gone forth, mingled with a few facts, giving just enough color of truth to make them seem plausible. This book has been written to clear away the veil of doubt that hangs around the origin of the Stars and Stripes.

The Continental Congress was very disturbed by the embarrassing situation of the colonies in 1775. After George Washington was appointed Commander-in-Chief of the Army, it showed its independence by appointing a committee composed of Benjamin Franklin, Benjamin Harrison, and Mr. Lynch to create a colonial flag that would be national in its tendency.

They finally decided on one with thirteen bars, alternate red and white, the "King's Colors," with the crosses of St. Andrew and St. George in a field of blue. The cross of St. Andrew, then, was white, while the cross of St. George was red. The colonies still acknowledged the sovereignty of England — as this flag attested — but united against her tyranny.

This was known as the "Grand Union Flag" — that is, the Union of the colonies- and was not created until after the committee had visited the camp at Cambridge and consulted with Washington. It was probably made either at the camp at Cambridge or in Boston, as Washington unfurled it under the Charter Oak on January 2, 1776. It received thirteen cheers and a salute of thirteen guns.

It is unknown whether Samuel Adams, the "Father of Liberty," was consulted about this flag. Still, it is a well-known fact that he was looking forward, even then, to the colonies' independence, while Washington, Franklin, and the others still looked for justice, tardy though it might be, from England.

Two days later, on January 4, 1776, Washington received the King's speech. As it happened to come so near the time of the adoption of the new flag, with the English crosses of St. Andrew and St. George, many of the regulars thought it meant submission, and the English seemed for the time to understand it; but our army showed great indignation over the King's speech to parliament and burned all of the copies.

In a letter of General Washington to Joseph Reed, written on January 4, he says:

We are at length favored with the sight of his majesty's most gracious speech, breathing sentiments of tenderness and compassion for his deluded American subjects. The speech I sent you (the Boston gentry sent out a volume of them) was farcical enough and gave great joy to them without knowing or intending it, for on that day (the 2nd), which gave being to our new army.

Still, before the proclamation came to hand, we hoisted the Union flag, in compliment to the United Colonies, but behold, it was received at Boston as a token of the deep impression the speech had made upon us and as a signal of submission. By this time, they begin to think it strange that we have not formally surrendered our lines.

At this time, the number and kinds of flags in use on land and sea were limited to the ingenuity of the state and military officials. This was very embarrassing. On May 20, 1776, Washington was requested to appear on important secret military business before Congress.

According to Washington's letters, Major-General Putnam was left in command at New York during his absence, in the latter part of May 1776. Washington, accompanied by Colonel George Ross, a member of his staff, and the Honorable Robert Morris, the great financier of the revolution, called upon Mrs. Betsy Ross, a niece of Colonel Ross.

She was a young and beautiful widow, only twenty-four years old, and known as an expert at needlework. They called to engage her services in preparing our first starry flag.

She lived in a little house on Arch Street, Philadelphia, which stands unchanged today, except for one large window, which has been placed in the front. In this house, Washington unfolded a paper on which had been rudely sketched a plan of a flag of thirteen stripes, with a blue field dotted with thirteen stars.

They discussed the plan for this flag and Airs in detail. Ross noticed that the sketched stars were six-pointed and suggested that they should have five points.

Washington admitted she was correct, but he preferred a star that was not an exact copy of the one on his coat of arms. He also thought that a six-pointed star would be easier to cut.

Mrs. Ross liked the five-pointed star, and to show that they were easily cut, she deftly folded a piece of paper and unfolded a perfect star with five points with one clip of her scissors.

(See the illustration below showing the way Betsy Ross folded the paper giving the five-pointed star which has ever since graced our country's banner.)

A, first fold of a square piece of paper; B, second; C, third, and D, fourth fold. The dotted line AA is the clip of the scissors.

There is no record that Congress acted on the national colors at this session, but Betsy Ross made the first flag. In this way, we find in Washington's letter of May 28, 1776, to General Putnam at New York, positive instructions "to the several colonels to hurry to get their colors done." In the orderly book, May 31, 1776, are these words:

"General Washington has written to General Putnam, desiring him in the most pressing terms, to give positive orders to all the colonels to complete colors for their respective regiments immediately."

The proof is positive that the committee approved Betsy Ross's finished flag. She was instructed to procure all the bunting possible in Philadelphia and make flags for the use of Congress, Colonel Ross furnishing the money.

It is easily understood how, on account of the meager resources of Congress and the unsettled condition of affairs generally, together with the fact that legislative action was extremely slow and tedious, Colonel Ross should expedite matters by defraying the expense of this first order for our national colors.

There is little, if any, doubt but that Washington on December 24, Christmas Eve, in 1776, carried the starry flag in making that perilous trip through ice and snow across Delaware, leading his sturdy, but poorly equipped troops.

How inspiring to look back to that night when the Massachusetts fishermen so skillfully managed the boats that the whole army was safely landed and in line for march at four o'clock on Christmas morning. The story of how they plodded on through ice and snow, surprising and defeating the Hessians and capturing a thousand men and their ammunition and equipment, is well known.

This was the battle of Trenton, which changed the whole aspect of the war, even causing Lord Cornwallis to disembark and again start in pursuit of Washington, whose cause he had so lately declared lost.

It is fitting here to speak of that friend of Washington, Robert Morris, one of the committee members who originated our national colors, the great patriot who, after the battle of Trenton, went from house to house, soliciting money from his friends to clothe and feed this glorious army, which had fought so well.

Congress was very slow to act and did not command even the meager resources of the different colonies. It lacked the centralized government that gives it such strength today.

Considering the grave questions affecting the people's life and liberty, it is not strange that the flag or any definite action regarding it was not given prompt consideration.

To indicate how slow Congress was to act regarding the flag, we have only to refer to the Congressional records, which show that the resolution for its adoption was dated over one year after it was actually created by the committee of which Washington was chief, on June 14, 1777.

However, a month previous to this, Congress sent Betsy Ross an order on the treasury for £14. 12s. 2d., for flags for the fleet in the Delaware River, and she soon received an order to make all the government flags. The first flag was made of English bunting, the same as today's bunting, except that our bunting now is manufactured at home.

There seems to be no question but that these colors, the stars and stripes, were unofficially adopted immediately after the completion of the first flag, the latter part of May 1776, and that they went into general use at once, so far as it was practicable under the conditions then existing.

Washington had the first flag created at this time. It was satisfactory, and he immediately instructed General Putnam to have the colonels prepare their colors — the colors that had just been approved, and which we know to be our flag of today.

The first reference we have of an English description of our flag is at the surrender of General Burgoyne, on October 17, 1777, when one of the officers said:

The stars of the new flag represent a constellation of states."

Mr. George Canby, an estimable gentleman of the old school and grandson of Betsy Ross, has been tireless and indefatigable in his research on the subject of our flag. He claims, as did his brother, Mr. William J. Canby, before him, that the first flag with stars and stripes went into immediate use after its inception in the latter part of May 1776.

Congress passed the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776, and some authorities, of whom Admiral Preble is the best, seem to infer that the Cambridge flag, with its English crosses, which Washington unfurled under the Charter Oak, was still carried by our armies until Congress took action in 1777.

That Washington or Congress would sanction the carrying of this flag after the Declaration of Independence seems absurd, and it is certainly against all proof, as well as against the records of the family whose ancestor made the first flag.

Peak's portrait of Washington at the Battle of Trenton, December 26 and 27, 1776, shows the Union Jack with the thirteen stars in the field of blue. Admiral Preble says, This is only presumptive proof that the stars were at that time in use on our flag, but Titian R. Peale, son of the painter, says:

"I visited the Smithsonian Institute to see the portrait of Washington painted by my father after the Battle of Trenton. The flag represented has a blue field with white stars arranged in a circle. I don't know that I ever heard my father speak of that flag, but I know he painted the trophies at Washington's feet from the flags then captured, which were left with him for the purpose."

He further says:

"He was always very particular in the matters of historic record in his pictures."

Preble admits this in his book but evidently thought that the artist Peak took the flag as it was then (1779) and not the flag of 1776, which the writer claims was identically the same.

Through persistent research, many facts have come to light that would doubtless have changed the opinion of the late Admiral Preble — facts that were unknown to him.

On Saturday, June 14, 1777, Congress finally officially adopted the flag of our Union and independence, to-wit:

Resolved, "That the flag of the thirteen United States be thirteen stripes, alternate red and white; that the Union is thirteen stars, white in the blue field, representing a new constellation."

There is not the slightest record in any of the manuscripts, journals, or motions in the Library of Congress, or in the original files or drafts in motions made in the continental Congress, of any previous legislative action for the establishment of a national flag for the United States of America, whose independence was declared nearly a year earlier.

Even after the flag's official adoption, it was not thoroughly brought before the people for many months. All of this adds to the proof that Congress was adopting and legalizing a flag that was in general use.

That there was no recorded discussion in Congress regarding adopting our flag was perfectly natural because the Star-Spangled Banner came with our independence and was officially acknowledged at this time (June 14, 1777).

There is some diversity of opinion as to how the red, white, and blue, arranged in the stars and stripes, came to be considered our flag.

The flag of the Netherlands, which is of red, white, and blue stripes, had been familiar to the pilgrims while they lived in Holland, and its three stripes of red, white, and blue were doubtless not forgotten. But it seems most probable that the coat of arms of the Washington family furnished more than a suggestion.

The coat of arms of his ancestors, which he had adopted, comprised the red, white, and blue* and the stars, and was familiar to all who were associated with Washington.

He brought the pencil drawing when, with the others, he called upon Mrs. Ross to have a suitable flag made. As we find no mention in history, records, or diaries as to who made the drawing, it seems conclusive that he himself designed and drew the plan from his own coat of arms, which was entirely different from England's colors, which had become necessarily distasteful.

It seems fitting in this place to write a little history regarding the Washington coat of arms, the earliest mention of which was by Lawrence Washington, worshipful mayor of Northampton, England, in 1532. In 1540, he placed it upon the porch of his manor house and on the tomb of Ann, his wife, in 1564.

At the old church in Brighton, England, the tombs of Washington's ancestors are marked by memorial plates of brass bearing the family arms, which consisted of a shield bearing the stars and stripes.

The Archeological Society of England, the highest authority on ancient churches and heraldic matters, states that from the red and white bars and stars of this shield and the raven issuant from its crest (borne later by General Washington), the framers of the Constitution took their idea of the flag.

When General Washington's great-grandfather, Sir John Washington, came to this country in 1657, he brought the family shield with him.

Sir John settled in Virginia and established the American line of Washington. Afterward, George Washington had it emblazoned upon the panels of his carriages, on his watch seals, bookmarks, and his dishes bore the same emblem.

Sources

The story of our flag, colonial and national, with a historical sketch of the Quakeress Betsy Ross, by Addie Guthrie Weaver. - 1898

The History Of The First United States Flag, And The Patriotism Of Betsy Ross, The Immortal Heroine Who Originated The First Flag Of The Union. By Col. J. Franklin Reigart, 1878. (PDF) Available online – 25.3 MB

Did Betsy Ross Design The Flag Of The United States of America? By Hanford, Franklin, 1844 (PDF) Available online – 13.7 MB

Leave a comment