Bunker Hill Flag (1775): History of the Famous Revolutionary War Banner

Bunker Hill Flag (1775): History of the Famous Revolutionary War Banner

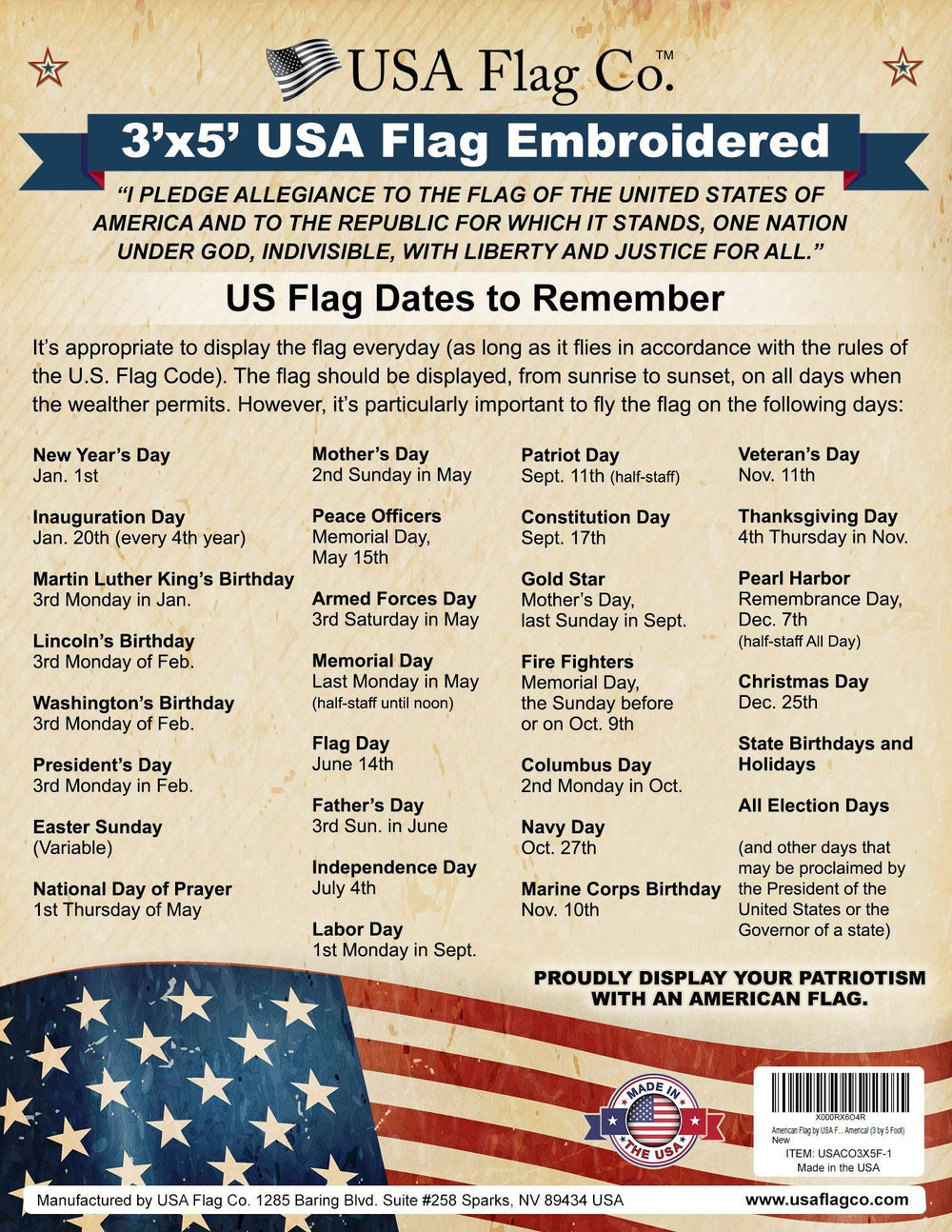

The blue Bunker Hill Flag. The blue field may be the result of an error in a wood engraving; the actual "Bunker Hill Flag" may have been the flag captioned "The Flag of New England during the Revolutionary War," as shown in the picture below [1].

Following the skirmishes with the Minutemen at Lexington and Concord, the British withdrew to Boston. On the night of June 16-17, 1775, the Americans fortified Breed's and Bunker Hill overlooking Boston Harbor.

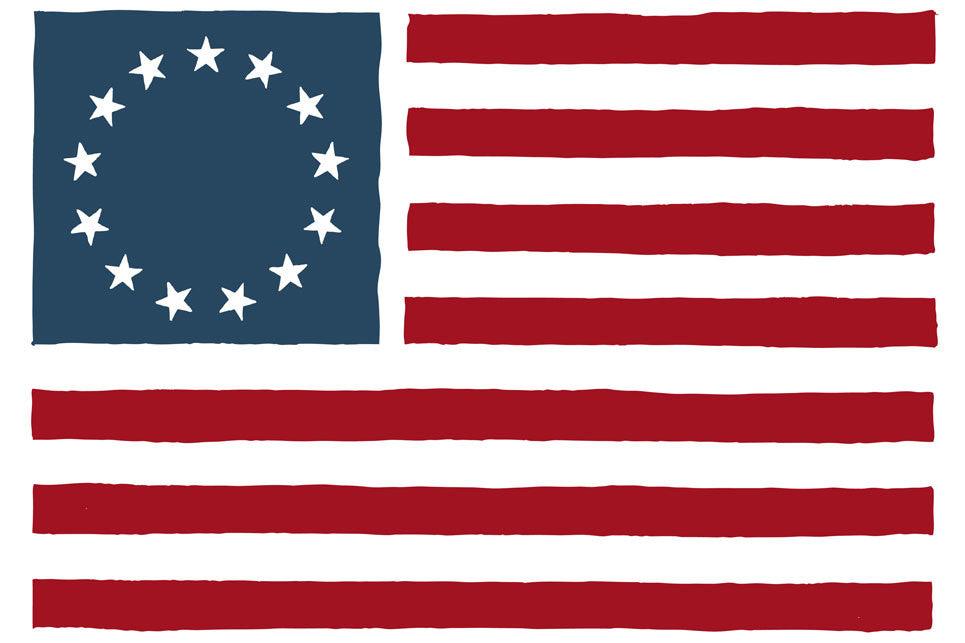

The Continental Flag, also known as The Flag of New England, was used during the Revolutionary War.

The next afternoon, the British landed 2,400 men. These advanced twice up the slope toward this early New England flag, only to be cut down by the well-disciplined volleys of the colonial militiamen.

The Americans, short of powder and shot, had to withdraw on the third assault–but not before they had felled almost half the British force.

As early as 1704, the colonies used a similar flag with a red field and sometimes an oak or pine tree in the canton.

[1] Continental Flag also known as The Flag of New England during the Revolutionary War. It was depicted by John Trumbull in The Death of General Warren at the Battle of Bunker's Hill, June 17, 1775. [2] This flag has also been adopted by the New England Revolution Major League Soccer team and The New England Independence Campaign.

The Flag of New England

In 1707, the colonists evinced a growing feeling of independence and began to depart from the authorized English standards. In 1704, the Pine Tree Flag was mentioned in New England. It is described in one form as a red flag with a white canton quartered, with the Red Cross of St. George having a green pine tree in the upper left quarter. Occasionally, the fly was blue.

Another form of the Pine Tree Flag, the one officially adopted by the Massachusetts Council in 1776, has a white field with the Pine Tree in the center and the words "An Appeal to Heaven" above it.

Battle of Bunker Hill

The following "full and correct account" of the Battle of Bunker Hill is taken from a pamphlet published in Boston, June 17, 1825.

After the affair at Lexington and Concord, on April 19, 1775, the people, animated by one common impulse, flew to arms in every direction. The husbandman changed his plowshare for a musket, and about 15,000 men, 10,000 from Massachusetts, and the remainder from New Hampshire,

Rhode Island and Connecticut, assembled under Gen. Ward, were in the environs of Boston. They were then occupied by 10,000 highly disciplined and well-equipped British troops under the command of Generals Gage, Howe, Clinton, Burgoyne, Pigot, and others.

The Battle of Bunker Hill, by Howard Pyle - [3] (Click image to enlarge size.)

Fearing an intention on the part of the British to occupy the critical heights at Charlestown and Dorchester, which would enable them to command the surrounding country, Col. Prescott was detached by his own desire, from the American camp at Cambridge, on the evening of June 16, 1775, with about 1000 militia, mostly of Massachusetts, including 120 men of Putnam's regiment from Connecticut, and one Artillery company, to Bunker Hill, with a view to occupy and fortify that post.

At this Hill, the detachment made a short halt but concluded to advance still nearer the British and accordingly took possession of Breed's Hill, a position that commanded the whole inner harbor of Boston.

Here, about midnight, they commenced throwing up a redoubt, which they completed, notwithstanding every possible effort from the British ships and batteries to prevent them, about noon the next day.

So silent had the operations been conducted through the night that the British had not the most distant notice of the Americans' design until daybreak presented to their view the half-formed battery and daring stand made against them.

A dreadful cannonade, accompanied by shells, was immediately commenced from the British battery at Copp's Hill, and the ships of war and floating batteries stationed in Charles River.

The break of day on June 17, 1775, presented a scene, which for daring and firmness could never be surpassed—1000 inexperienced militia, in the attire of their various avocations, without discipline, almost without artillery and bayonets, scantily supplied with ammunition, and wholly destitute of provisions, defying the power of the formidable British fleet and army, determined to maintain the liberty of their soil, or moisten that soil with their blood.

Without aid, however, from the main body of the army, it seemed impossible to maintain their position—the men having been without sleep, toiling through the night, and destitute of the necessary food required by nature, had become nearly exhausted.

Throughout the morning, representations were repeatedly made to Headquarters regarding the necessity of reinforcements and supplies.

Major Brooks, the late revered Governor of Massachusetts, who commanded a battalion of minutemen at Concord, set out for Cambridge about 9 o'clock, on foot, it being impossible to procure a horse, soliciting succor. Still, as there were two other points exposed to the British, Roxbury and Cambridge, then the Head Quarters, at which place all the little stores of the army were collected, and the loss of which would be incalculable at that moment, great fears were entertained lest they should march over the neck to Roxbury, and attack the camp there, or pass over the bay in boats, there being at that time no artificial avenue to connect.

Boston, with the adjacent country, attacked the Headquarters and destroyed the stores; it was therefore deemed impossible to afford any reinforcement to Charlestown Heights until the movements of the British rendered evidence of their intention certain.

The fire from the Glasgow frigate and two floating batteries in Charles River was wholly directed—with a view to preventing any communication—across the isthmus that connects Charlestown with the mainland. This kept up a continued shower of missiles and rendered communication truly dangerous to those who should attempt it.

When the intention of the British to attack the heights of Charlestown became apparent, the remainder of Putnam's regiment. Col. Gardner's regiment, both of which, as to numbers, were very imperfect, and some New Hampshire Militia, marched, notwithstanding the heavy fire across the neck, for Charlestown Heights, where they arrived much fatigued, just after the British had moved to the first attack.

The British commenced crossing troops from Boston about 12 o'clock, and landed at Moreton's Point, S.E., from Breed's Hill.

At 2 o'clock, from the best accounts that can be obtained, they had landed between 3 and 4,000 men under the immediate command of Gen. Howe, and formed, in apparently invincible order, at the base of the Hill.

Battle of Bunker Hill, Boston, Massachusetts, 1775--Maps--Early works to 1800. Includes "References" to points of military interest in different hand and ink.

The position of the Americans at this time was a redoubt on the summit of the height of about eight rods square, and a breastwork; extending on the left of it, about seventy feet down the eastern declivity of the Hill.

This redoubt and breastwork was commanded by Prescott in person, who had superintended its construction, and who occupied it with the Massachusetts Militia of his detachment, and a part of Little's regiment, which had arrived about one o'clock.

They were dreadfully deficient in equipment and ammunition and had been toiling incessantly for many hours. Some accounts say it, even then were destitute of provisions.—A little to the eastward of the redoubt, and northerly to the rear of it, was a rail fence, extending almost to Mystick river,—to this fence another had been added during the night and forenoon, and some newly mown grass thrown against them, to afford something like a cover to the troops.—At this fence the 120 Connecticut Militia were posted.

The movements of the British made it evident they intended to march a substantial column along the margin of the Mystick, and turn the redoubt on the north, while another column attacked it in front; accordingly, to prevent this design, a large force became necessary at the breastwork and rail fence.

The reinforcements that arrived, amounting to about 800 or 1000 men, were ordered by Gen. Putnam, who had been extremely active throughout the night and morning and had accompanied the expedition to this point.

At this moment thousands of persons of both sexes had collected on the Church steeples, Beacon Hill, house tops, and every place in Boston and its neighborhood, where a view of the battle ground could be obtained, viewing with painful anxiety, the movements of the combatants—wondering, yet admiring the bold stand of the Americans, and trembling at the thoughts of the formidable army marshaled in array against them.

Before 3 o'clock, the British formed, in two columns, for the attack—one column, as had been anticipated, moved along the Mystic River, with the intention of taking the redoubt in the rear, while the other advanced up the ascent directly in front of the redoubt, where Prescott was ready to receive them.

General Joseph Warren, President of the Provincial Congress and of the Committee of Safety, who had been appointed but a few days before a Major General of the Massachusetts troops, had volunteered on the occasion as a private soldier, and was in the redoubt with a musket, animating the men, by his influence and example, to the most daring determination.

The Americans were ordered to reserve their fire until the enemy advanced sufficiently near to make their aim certain.

Several vollies were fired by the British with but little success; and so long a time had elapsed, and the British were allowed to advance so near the Americans without their fire being returned, that a doubt arose whether or not the latter intended to give battle —but the fatal moment soon arrived:—when the British had advanced to within about eight rods, a sheet of fire was poured upon them and continued a short time with such deadly effect that hundreds of the assailants lay weltering in their blood, and the remainder retreated in dismay to the point where they had first landed.

From daylight to the time the British advanced on the works, an incessant fire had been kept up on the Americans from the ships and batteries—this fire was now renewed with increased vigor.

After a short time, the British officers succeeded in rallying their men and again advanced in the same order as before to the attack.

Thinking to divert the attention of the Americans, the town of Charlestown, consisting of 500 wooden buildings, was now set on fire by the British—the roar of the flames, the crashing of falling timbers, the awful appearance of desolation presented, the dreadful shrieks of the dying and the wounded in the last attack, added to the knowledge of the formidable force advancing against them, combined to form a scene apparently too much for men bred in the quiet retirement of domestic life to sustain—but the stillness of death reigned within the American works —and naught could be seen but the deadly presented weapon, ready to hurl fresh destruction on the assailants.

The fire of the Americans was again reserved till the British came still nearer than before, when the same unerring aim was taken. The British shrank, terrified, from before its fatal effects, flying, completely routed, a second time to the banks of the river, and leaving, as before, the field strewed with their wounded and their dead.

Again, the ships and batteries renewed their fire and kept a continual shower of balls on the works. Notwithstanding every exertion, the British officers found it impossible to rally the men for a third attack; one third of their comrades had fallen, and finally it was not till a reinforcement of more than 1000 fresh troops, with a strong park of artillery, had joined them from Boston, that they could be induced to form anew.

In the meantime, every effort was made on the part of the Americans to resist a third attack; Gen. Putnam rode, notwithstanding the heavy fire of the ships and batteries, several times across the neck to induce the militia to advance, but it was only a few of the resolute and brave who would encounter the storm.

The British receiving reinforcements from their formidable main body—the town of Charlestown presenting one wide scene of destruction—the probability the Americans must shortly retreat—the shower of balls pouring over the neck—presented obstacles too appalling for raw troops to sustain, and embodied too much danger to allow them to encounter.—Yet, notwithstanding all this, the Americans on the heights were elated with their success, and waited with coolness and determination the now formidable advance of the enemy.

Once more the British, aided by their reinforcements, advanced to the attack, but with great skill and caution—their artillery was planted on the eastern declivity of the Hill, between the rail fence and the breast work, where it was directed along the line of the Americans, stationed at the latter place, and against the gate way on the north eastern corner of the redoubt—at the same time they attacked the redoubt on the south eastern and south western sides, and entered it with fixed bayonets.

The slaughter on their advancing was great, but the Americans, not having bayonets to meet them on equal terms and their powder exhausted, slowly retreated, opposing and extricating themselves from the British with the butts of their pieces.

The column that advanced against the rail fence was received most dauntlessly. The Americans fought with spirit and heroism that could not be surpassed, and had their ammunition have held out, would have secured to themselves a third time the palm of victory; as it was, they effectually prevented the enemy from accomplishing his purpose, which was to turn their flank and cut the whole of the Americans off; but having become perfectly exhausted, this body of the Americans also slowly retired, retreating in much better order than could have been expected from undisciplined troops. Those in the redoubt had extricated themselves from a host of bayonets surrounded by them.

The British followed the Americans to Bunker Hill, but some fresh militia, coming up to the latter's aid at this moment, covered their retreat.

The Americans crossed Charlestown Neck about 7 o'clock, having performed deeds that seemed almost impossible in the last twenty hours. Some of them proceeded to Cambridge, and others posted themselves quietly on Winter and Prospect Hills.

From the most accurate statements, it appears the British must have had nearly 5,000 soldiers in the battle, with between 3 and 4000 having first landed and the reinforcement amounting to over 1,000.

Throughout the day, the Americans did not have 2,000 men on the field.

The slaughter on the side of the British was immense, having had nearly 1,500 killed and wounded; twelve hundred of which were either killed or mortally injured,—the Americans about 400.

Had the Commanders at Charlestown Heights become terrified on being cut off from their main body and supplies, and surrendered their army, or even retreated before they did, from the terrific force that opposed them, where would have now been that ornament and example to the world, the Independence of the United States?—When it was found that no reinforcements were to be allowed them, the most sanguine man on that field could not have even indulged a hope of success, but all determined to deserve it—and although they did not obtain a victory, their example was the cause of a great many.—The first attempt on the commencement of a war is held up, by one party or the other, as an example to those that succeed it, and a Victory or Defeat, though not, perhaps, of any significant magnitude in itself, is most potent and vital in its effects.

Had such conduct as was here exhibited been, to any degree, imitated by the immediate Commander at the first military onset of the last war, how truly different a result would have been to the fatal one that terminated that unfortunate expedition.

From the immense superiority of the British, at this stage of the war, having a large army of highly disciplined and well equipped troops, and the Americans possessing but few other munitions or weapons of war, and but little more discipline, than what each man possessed when he threw aside his plough and took the gun that he had kept for pastime or for profit, but now to be employed for a different purpose, from off the hooks that held it,—perhaps it would have been in their power, by pursuing the Americans to Cambridge, and destroying the few stores that had been collected there, to implant a blow which could never have been recovered from, but they were utterly terrified.

The awful lesson they had just received filled them with horror, and the blood of 1,500 of their companions, who fell on that day, presented to them a warning which they could never forget.

From the Battle of Bunker Hill sprang the protection and the vigor that nurtured the Tree of Liberty, and in all probability, our Independence and Glory may be ascribed to it.

The name of the first martyr who gave his life for the good of his country on that day, in the moment's importance, was lost; otherwise, a monument, in connection with the gallant Joseph Warren, should be raised in his memory.

Col. Prescott thus related the manner of his death:

"The first man who fell in the Battle of Bunker Hill was killed by a cannonball, which struck his head. He was so near me that my clothes were besmeared with his blood and brains, which I wiped off in some degree, with a handful of fresh earth. The sight was so shocking to many men that they left their posts and ran to view him. I ordered them back, but in vain. I then ordered him to be buried instantly. A subaltern officer expressed surprise that I should allow him to be buried without having prayers said; I replied, This is the first man that has been killed, and the only one that will be buried today. I put him out of sight so the men may be kept in their places. God only knows who, or how many of us, will fall before it ends. To your post, my good fellow, let each man do his duty."

The name of the patriot who thus fell is supposed to have been Pollard, a young man belonging to Billerica. He was struck by a cannonball thrown from the line of battle ship Somerset.

Sources

History of the Battle of Breed's Hill, by Major-Generals William Heath, Henry Lee, James Wilkinson, and Henry Dearborn. Compiled by Charles Coffin, 1779-1851. Saco, Printed by W.J.Condon, 1831. (PDF) Available online. - 18.5 MB

A History of Breed's (commonly called) Bunker's Hill Battle, Fought Between The Provincial Troops and the British, June 17, 1775. By Oliver Morsman, ESQ. A Revolution Soldier. Sacket's Harbor: Printed By Truman W. Haskeld, 1830. (PDF) Available online. - 17.3 MB

The Battle of Bunker Hill, by Howard Pyle [3]

Leave a comment