Come and Take It Flag (1835): History of the Texas Revolution Banner

The "Come and Take It" Flag: Symbol of Defiance at the Battle of Gonzales (1835)

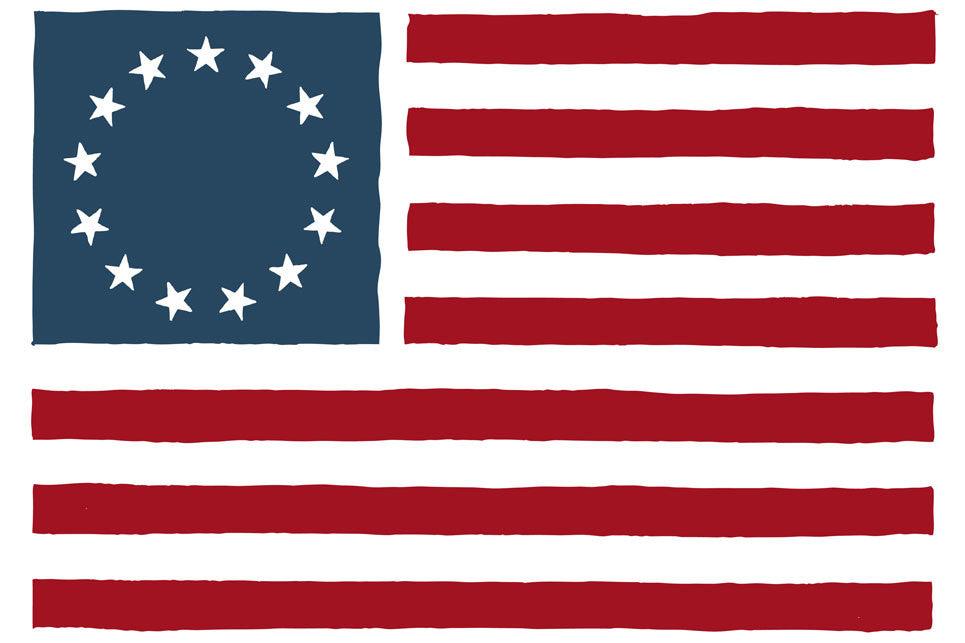

The museum mural shown below shows Texan soldiers holding the Come and Take It flag and fighting in the Battle of Gonzales, which was referred to as the "Lexington of Texas."

The Battle of Gonzales was the first military engagement of the Texas Revolution. It was fought on the west side of the Guadalupe River about four miles outside of Gonzales, Texas, on October 2, 1835, between rebellious Texian settlers and a detachment of Mexican army soldiers.

Texians flew the " Come and Take It flag before the battle of Gonzales.

Come and Take It Flag

Date: October 2, 1835

Location: Gonzales, Texas

Result: Texian victory, Mexican withdrawal, beginning of the Texian rebellion against the Mexican government

THE BATTLE OF GONZALES, THE "LEXINGTON" OF THE TEXAS REVOLUTION

MILES S. BENNET,

Captain Company E, Texas Ex-Rangers Battalion.

On July 4, 1838, at Gonzales, I met at a festive occasion some of those who had been prominent in the defense of that town and its brass cannon in 1835; and associating with them and others for many years afterward, I had opportunities for hearing from them narratives of stirring incidents of that period.

Although these incidents were considered of little importance at the time, I like to recall them and record them so that they may not be completely forgotten.

In the company of my father. Major Valentine Bennet, who had actively participated in those scenes, was one of the first officers commissioned at Gonzales by General Stephen F. Austin.

I went to some of the places of the vicinity made historic by the movements of the colonists and the events of the battle and retreat, notably the celebrated mound (De Witt's) where the Mexicans encamped: also, the prairie bluff below the town watering-place just above where the timbered bottom begins, the place where the cannon was thrown into the river when the retreating army burned the city, and the stricken inhabitants terribly weakened by the slaughter in the Alamo of forty of their men, were constrained to abandon the place and try to save themselves in the disastrous flight known as the "Runaway Scrape."

It occasioned melancholy feelings to view the ruins of the burnt town, which had evidently been quite a thriving little city. It had comfortable two-story dwellings, storehouses said to have been stocked with valuable goods, a cotton gin and mills, and a brickyard, and it could boast of regular city incorporation.

My father was acquainted with the circumstances attending the beginning of hostilities at Gonzales, having located there with some colonists in 1832.

He had been in feeble health, having been severely wounded in the battle of Velasco in June of that year.

He had been acquainted with the forty citizens who had ridden to the front and fought and fallen in the Alamo a few days before the time when Gonzales, being deprived of so many of her protectors, was also wantonly sacrificed to the flames.

Our people should never cherish the memory of those heroes of the Alamo. I record here the names of some of those who went from Gonzales: Capt. Albert Martin, George W. Cottle, Almerion Dickinson, William Dearduff, James George, John E. Garvin, Thomas Jackson, George C. Kimble, Andrew Kent, William King, Jacob C. Darst, William Fishbaugh, Thomas R. Miller, Jesse McCoy, Isaac Milsap, Isaac Baker, John E. Gaston, Robert White, Galby Fuqua, Amos Pollard, John Cane, Dolfin Floyd, Charles Despalier, Claib. Wright, George Tumlinson, Johnnie Kellogg.

I became acquainted with the survivors of some of the families of these men after their return to Guadaloupe.

In 1831, the colonists of DeWitt's settlement were furnished with a brass six-pounder, which was kept at Gonzales, for their defense against the Indians.

From rumors that had been heard, the apprehensions of the settlers were excited; and, when, in the latter part of September 1835, Colonel Ugartechea, commanding the Mexican forces at San Antonio, sent a small troop of cavalry with an order for the delivery of the piece, it was resolved by the inhabitants not to give up the gun.

The order was directed to Andrew Ponton, the alcalde, and Wiley Martin, the political chief at Gonzales. Lieutenant Castafieda brought it, with ten men and an ox cart to carry away the unmounted cannon.

In order to gain time, the citizens delayed the Mexicans with evasive answers for two or three days, sending Matthew Caldwell to Colorado and Washington for reinforcements.

They also secreted the ferry boat in the slough branch in the timber bottom above the town, and on the first day, they mustered eighteen men whose names are as follows: Capt. Albert Martin, Jacob C. Darst, Winslow Turner, W. W. Arrington, Graves Fulcher, George W. Davis, John Sowell, James Hinds, Thomas Miller, Valentine Bennet, Ezekiel Williams, Simeon Bateman, J. D. Clements, Almerion Dickinson, Benjamin Fuqua, Thomas Jackson, Charles Mason, Almon Cottle.

Afterward, when I became acquainted with some of this little band of eighteen survivors and heard their narrative of this part of the history, I noticed with what honest pride they referred to it. And the gratification of being able to say, "I was one of the 'Old Eighteen' defenders of Gonzales."

Some of the families secreted themselves in the timbered bottoms. Jesse McCoy, Joseph Kent, Graves Fulcher, and W. W. Arrington kept watching the river. Afterward, Mr. Kent told me how he and Fulchear, in their hiding places, could scarcely resist the temptation to shoot at the Mexicans as they came to the opposite bank to water their animals.

Texian scouts were sent out in the direction of San Antonio, as it was known that the Mexicans encamped at DeWitt's Mound had sent couriers to the west, and that probably they had been informed by a half-friendly Indian who had been loitering about the town of the preparations made there for defense.

The naked cannon was at first buried in Geo. W. Davis's peach orchard, the ground being plowed and smoothed over. Then, a broad-tired ox wagon was fitted up, and the gun was raised and mounted upon it. Mr. Darst, Jno. Sowell, Dick Chisholm, and others worked diligently at it.

Afterward, Mr. Chisholm narrated to me how he and Mr. Sowell (both blacksmiths) prepared shots for the cannon by cutting up pieces of chains and forging iron balls out of scraps they could procure.

In the short space of forty-eight hours, Matthew Caldwell returned from the east with help. Upon the arrival of Mexican reinforcements, increasing their number to about two hundred, their Lieutenant, Castafieda, with a troop, was sent with despatches directed to the alcalde of Gonzales, but could not cross the Guadaloupe as the boat had been secreted.

The officer was told that the alcalde was not in town, but that a messenger might swim over with the despatches without molestation, which was immediately done.

The Texian force, now increased to about one hundred fifty men, was organized under the command of John H. Moore and drilled diligently. The Ferryboat was returned to its landing, and a message was sent to the Mexican commander that the alcalde had returned to Gonzales and invited him to come over and get the cannon.

Upon hearing this, the officer, shrugging his shoulders, replied:

I suppose I need not go if I do not want."

The enemy started on their return to San Antonio, marched about seven miles, and encamped for the night at Ezekiel Williams's place. They robbed it and supplied themselves with many sacks of watermelon.

Museum mural of Texian soldiers holding the Come and Take It flag and fighting in the Battle of Gonzales, which was referred to as the "Lexington of Texas" because it was the first battle of the Texas Revolution.

On the night of October 1, the Texians crossed the river with their cannon, formed a council of war, and listened to a patriotic address from Rev. WV. P. Smith, a Methodist preacher of Rutersville.

Then they marched up the river several miles, and towards morning on October 2, a dense fog prevailing, their pickets encountered the mounted pickets of the enemy. A ludicrous firing and scattering ensued, neither force being able to distinguish friend from foe.

The Texians, however, were annoyed by a little dog that ran among them, betraying their position. A slight lifting of the fog showed the Mexican encampment, and an American known as Dr. Smithers came out calling, "Don't shoot, don't shoot.

I have a message;" but the colonists firing their cannons charged up and put the Mexicans to flight, capturing much of the camp's equipment.

My father told me that the roar of the cannon loaded with cut-up pieces of chains, reverberating along the valleys and river in the early morning, was remarkable. Some blood was seen, and crippled animals were left on the battleground.

In the division of the camp spoils, my father procured an excellent Spanish blanket of great value to him in the following campaign, in which he took an active part.

Remaining with the troops, Gen. S. F. Austin requested him to drill the men, and he was appointed lieutenant. He was among those first commissioned at Gonzales.

He was at the battle of Concepcion on October 28, and afterward, he took me over the battleground, showing me the positions of the troops.

He also received from General Austin the appointment of assistant quartermaster general, as is seen from Scarff's Comprehensive History of Texas, Vol. 1, page 541, where the surname printed "Baker" should doubtless be Bennet; and at the siege of Bexar, he was complimented for his efficient services in that memorable campaign by the commander in chief, Gen. Ed. Burleson, whose Report may be found in the History of Texas by Jno. Henry Brown, Vol. 1, page 424.

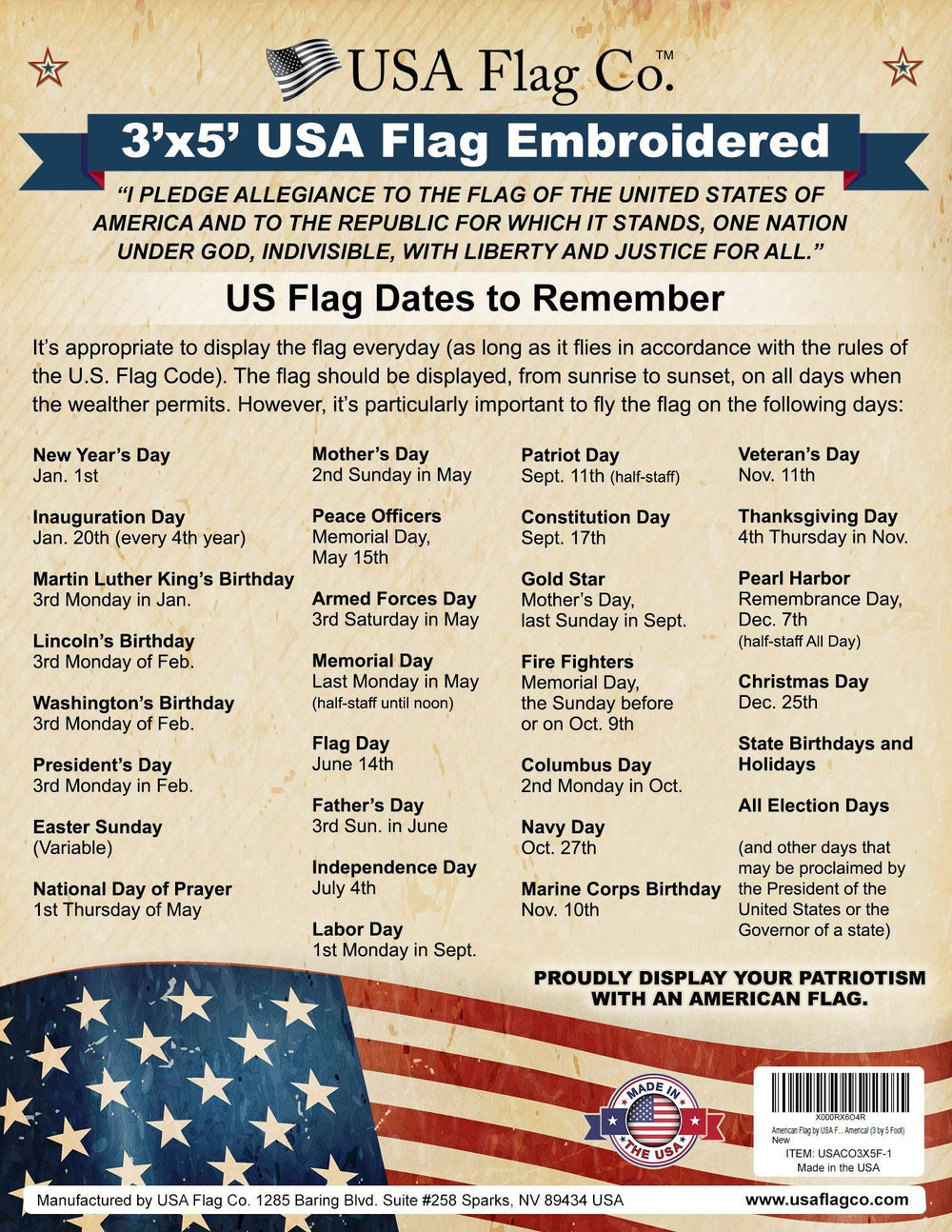

The "Come and Take It flag" and cannon of the Battle of Gonzales of the Texas Revolution.

Gonzales "Come and Take It" Flag - The text says "Come and Take It" by Daniel Mayer

Battle of Gonzales 1835 Picture | Mr. Adams Texas History Class in 2019 | Texas Revolution, Mexican-American War

Source:

The Quarterly of the Texas State Historical Association, Vol. 2, No. 4 (April 1899), pp. 313-316 Published by: Texas State Historical Association

Leave a comment