Grand Union Flag (1775): History of America's First National Banner

America's First National Flag: Hoisted by Washington at Cambridge (1776)

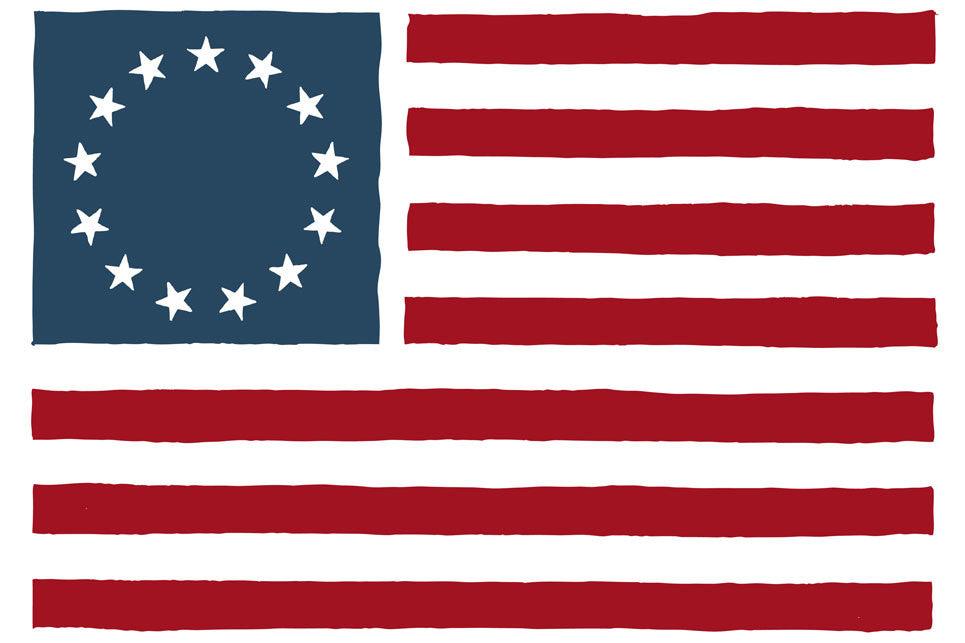

The first colonist flag to resemble the present Stars and Stripes was the Grand Union Flag, also known as the Cambridge Flag, the First Navy Ensign, the Congress Flag, and the Continental Colors. It is considered to be the first national flag of the United States.

The Grand Union flag consisted of 13 red and white stripes, with the British Union Flag of the time (before including St. Patrick's cross of Ireland) in the canton. It was first flown on December 3, 1775, by John Paul Jones (then a Continental Navy lieutenant) on the ship Alfred in Philadelphia.

In 1776 and early 1777, the American Continental forces used the Alfred flag as a naval ensign and garrison flag.

It is widely believed that the flag was raised by George Washington's army on New Year's Day 1776 at Prospect Hill in Charlestown (now part of Somerville), near his headquarters at Cambridge, Massachusetts, and that British observers interpreted the flag as a sign of surrender.

The Grand Union flag's design is similar to the British East India Company (BEIC) flag.

Indeed, specific BEIC designs since 1707 (when the canton was changed from the flag of England to that of Great Britain) have been identical, although the number of stripes has varied from 9 to 15.

The fact that BEIC flags were potentially well known by the American colonists has been the basis of a theory about the origin of the Grand Union flag's design.

The Flag Act of 1777 authorized the official national flag, which has a design similar to that of the Grand Union. It has thirteen stars (representing the original thirteen United States) on a field of blue, replacing the British Union flag in the canton.

Today, the Grand Union flag is often included as the "first flag" in United States flag history displays.

The Grand Union

Our flag — "The grand union" excerpt from a book written by Barlow Cumberland ... Brookline, Mass. 1926.

MAILED AT SUGGESTION OF ROGER PRESTON. PRESIDENT, ROTARY CLUB BOSTON, MASS.

Compliments of George C. Warren 253 Kent st., Brookline, Mass 1926

1. Grand Union 1776

2. United States 1777

3. United States 1897

OUR FLAG—"THE GRAND UNION"

EXCERPT FROM A BOOK WRITTEN BY Barlow Cumberland — "History of the Union Jack" Chap. II.

He (George Washington) first suggested an existing colonial design for this purpose, which had a 'white ground with a tree in the middle' and the motto, 'Appeal to Heaven.'

"This was succeeded by a new design for the continental union flag (6), which, on January 2, 1776, was raised by Washington over the camp of his army at Cambridge, Massachusetts, being the occasion of its first appearance.

"This flag was called 'The Grand Union' (pl. III, fig. 1). It was composed of thirteen stripes of alternate white and red, one for each colony, and in the upper corner was the British Union Jack of that time, having the two crosses of St. George and St. Andrew on a blue ground.

"The retention of the Union Jack in the new flag was intended to signify that the colonies retained their allegiance to Great Britain, although they were contesting the methods of government.

"The first flag then raised by Washington over the armies of the United States displayed the British Union Jack. We shall presently see the source from which the idea of the subsequent design arose.

"On July 4, 1776, the Declaration of Independence followed, but the Grand Union continued to be used. It was not until June 14, 1777, or almost a year after that event, that a new national flag was finally developed.

"The Congress of the United States, then meeting at Philadelphia, approved the report of a committee which had been appointed to consider the subject, and enacted, 'That the flag of the thirteen United States be thirteen stripes, alternate red and white; that the Union is thirteen stars, white in a blue field, representing a new constellation.' A further delay ensued, but at length, this flag was officially proclaimed on September 3, 1777, as the Union Flag of the United States (pl. III., fig. 2), and was the first national flag adopted by the authority of Congress.

"As Washington suggested, the design and introduction of the second, it is not improbable, and, indeed, it is recorded that he had something to do with the design of the final one."

Our Flag — The Grand Union Flag

A Brief History of our Grand Union Flag

We have shown that Congress's first legislation on the subject of a federal navy was in October 1775, and that after that, national cruisers were equipped and sent to sea on a three-month cruise; but so far as we can learn, they were without any provision for a national ensign and probably wore the colors of the state they sailed from.

Before the close of the year, Congress, as we have seen, had authorized a regular navy of seventeen vessels varying in force from ten to thirty-two guns, established a general prize law in consequence of Mowatt's burning of Falmouth, regulated the relative rank of military and naval officers, and established the pay of the navy, and appointed December 22, 1775.

Esek Hopkins, commander in chief of the embryo republic's naval forces, fixed his pay at 125 dollars a month.

At the same time, captains were commissioned to the Alfred, Columbus, Andrea Doria, Cabot, and Providence, [1] and first, second, and third lieutenants were appointed to each vessel.

The Alfred was a stout merchant ship originally called the Black Prince, and commanded by J. Barry.

She arrived in Philadelphia on October 13 and was purchased and armed by the committee. The Columbus, originally the Sally, was first purchased by the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety and ten days later sold to the naval committees of Congress. I have been unable to ascertain the merchant names of the other ships.

Notwithstanding the equipping of this fleet, the necessity of a common national flag seems not to have been thought of until Doctor Franklin, Mr. Lynch, and Mr. Harrison were appointed to consider the subject and assembled at the camp at Cambridge.

The result of their conference was the retention of the King's Colors or Union Jack, representing the yet recognized sovereignty of England, coupled with thirteen stripes of alternate red and white emblematic of the Union of the thirteen colonies against its tyranny and oppression, in place of the hitherto loyal red ensign.

The Grand Union Flag - 1776. Fac Simile of the Flag of the Schooner Royal Savage. Drawn in July 1776. From the Original Found By B.J. Lossing in the Schuyler Papers.

The new striped flag was hoisted over the camp at Cambridge for the first time on the 1st or 2d of January 1776. Gen. Washington, writing to Joseph Reed on January 4, says:

We are at length favored with the sight of his majesty's most gracious speech breathing sentiments of tenderness and compassion for his deluded American subjects; the speech I send you (a volume of them was sent out by the Boston gentry), and farcical enough we gave great joy to them without knowing or intending it, for on that day (the 2d) which gave being to our new army.

Still, before the proclamation, we hoisted the union flag to complement the United Colonies. But behold, it was received at Boston as a token of the deep impression the speech had made upon us, and as a signal of submission. By this time, they begin to think it strange that we have not formally surrendered our lines.

An anonymous letter, written under the date January 2, 1776, says:

The grand union flag of thirteen stripes was raised on a height near Boston. The regulars did not understand it, and as the king's speech had just been read as they supposed, they thought the new flag was a token of submission."

The captain of a British transport writing from Boston to his owners in London, on January 17, 1776, says,

I can see the rebels' camp very plain, whose colors, a little while ago, were entirely red; but on receiving the king's speech, which they burnt, they hoisted the Union flag, which is here supposed to intimate the Union of the provinces."

The British Annual Register says,

"They burnt the king's speech, and changed their colors from a plain red ground, which they had hitherto used, to a flag with thirteen stripes as a symbol of the Union and number of the colonies."

A letter from Boston in the Pennsylvania Gazette says:

"The grand union flag was raised on the 2d, in compliment to the United Colonies,"

"A British lieutenant writing from Charleston Heights, January 25, 1776, mentions the same fact and adds it was saluted with thirteen guns and thirteen cheers."

Botta, in his History of the American Revolution, derived from contemporary documents, writes thus:

The hostile speech of the king at the meeting of parliament had arrived in America, and copies of it were circulated in the camp. It was also announced there that the first petition of Congress had been rejected. The whole army manifested the utmost indignation at this intelligence. The royal speech was burnt in public by the infuriated soldiers.

At this time, they changed the red ground of their banners and striped them with thirteen stripes, as an emblem of their number and the Union of the colonies.

We have here contemporary evidence enough as to the time and place when "the grand union striped flag" was first unfurled, but it will be observed that nowhere is mention made of the color of the stripes that were placed on the previously red flag, the character of its Union, or anything other than presumptive evidence that it had a union.

Bancroft, in his recent History of the United States, describes this flag as the tricolored American banner, not yet spangled with stars, but showing thirteen stripes alternate red and white in the field, and the united crosses of St. George and St. Andrew, on a blue ground in the corner.

Still, he fails to furnish his authority for this statement. Fortunately, we can provide corroborative evidence that his statement is correct.

Since the publication of Bancroft's History, the eminent American historian Mr. Benson J. Lossing has found among the papers of Major Gen.

Philip Schuyler has a watercolor sketch of the Royal Savage, one of the little fleets on Lake Champlain, commanded by Benedict Arnold in the summer and winter of 1776.

This drawing is known to be the Royal Savage because it is endorsed in General Schuyler's handwriting as Captain Wynkoop's schooner, and Captain, or rather Colonel, Wynkoop is known to have commanded her at that time.

The drawing does not have a date, but it may be considered to settle all the characteristic features of the new flag.

At the head of the main topmast of the schooner, there is a flag precisely like the one described by Bancroft, and it is the only known contemporaneous drawing of it extant.

Through Mr. Lossing's kindness, I can give a facsimile in size, form, and color from the original of this interesting drawing. [2] (Plate VII).

Sources

[1] John Adams, a Marine Committee of Congress member, gives the following reasons for choosing these names: "This committee soon purchased and fitted five vessels.

The first was named Alfred, in honor of the founder of the greatest navy.

The second is Columbus, after the discoverer of this quarter of the globe.

The third is Cabot, for the discoverer of the northern part of this continent.

The fourth, Andrew Doria, in honor of the great Genoese admiral; and the fifth, Providence, for the name of the town where she was purchased, the residence of Governor Hopkins and his brother Esek, whom we appointed the first captain."

[2] Mr. Lossing informs me that in his forthcoming life of Schuyler, he intends to reproduce a facsimile drawing of the whole schooner.

Leave a comment