Star Spangled Banner Flag (1795): History of the 15-Star, 15-Stripe Banner

The Flag Over Fort McHenry: Mary Pickersgill's Banner and Francis Scott Key's Anthem

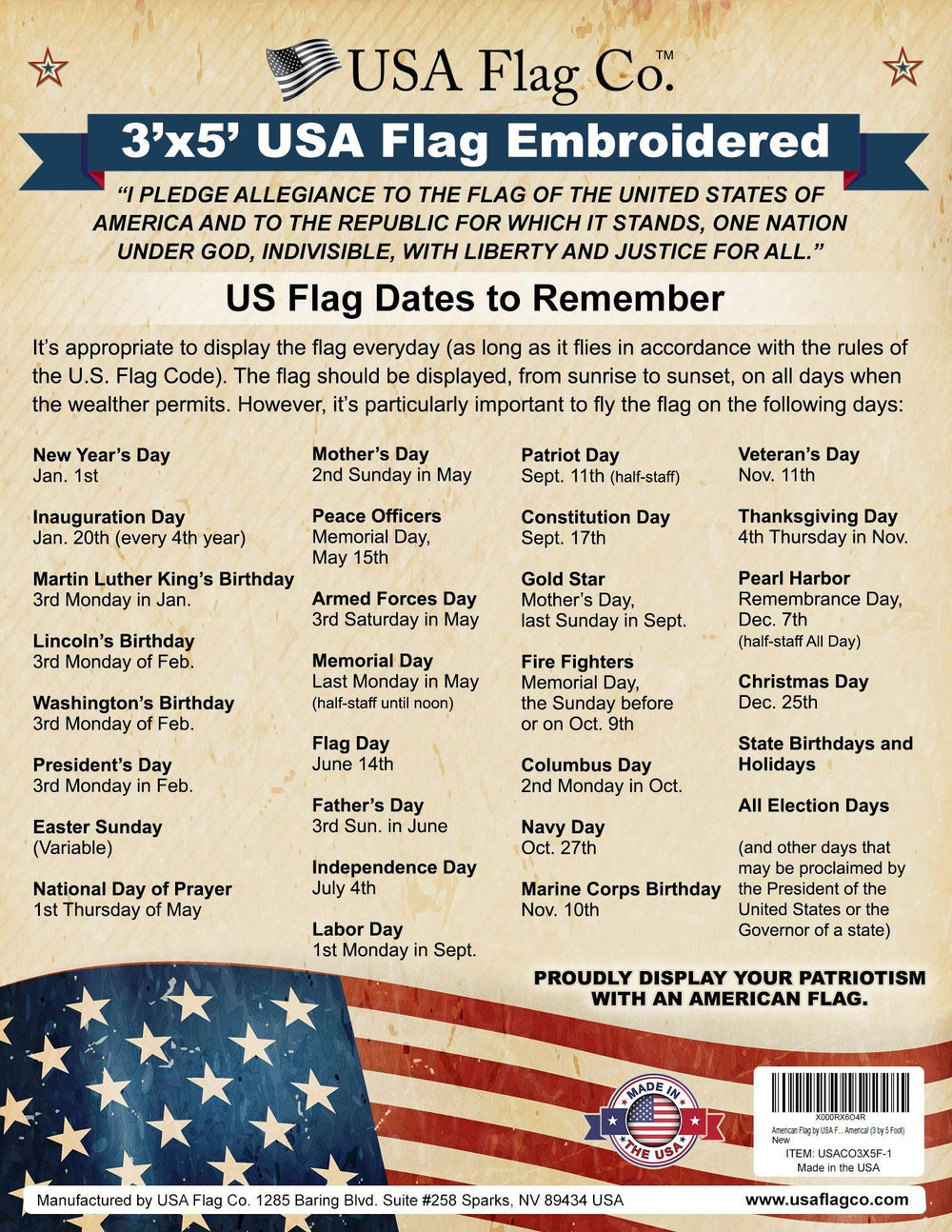

This 15 Star and 15 Stripe flag, known as the "Star-Spangled Banner flag," became the Official United States Flag on May 1, 1795. Two stars were added for the admission of Vermont (the 14th State on March 4, 1791) and Kentucky (the 15th State on June 1, 1792), and it was to last for 23 years.

The five Presidents who served under the Star Spangled Banner flag were;

- George Washington (1789-1797)

- John Adams (1797-1801)

- Thomas Jefferson (1801-1809)

- James Madison (1809-1817)

- James Monroe (1817-1825)

Flag Act of January 13, 1794

The 15-star and 15-stripe Flag was authorized by the Flag Act of January 13, 1794, adding two stripes and two Stars. The regulation went into effect on May 1, 1795. The Star-Spangled Banner flag was the only U.S. Flag to have more than 13 stripes.

Francis Scott Key immortalized it during the bombardment of Fort McHenry on September 13, 1814.

Brigadier General John Strieker ordered and made the Star-Spangled Banner, which triumphantly waved over Fort McHenry on September 13 and 14, 1814, and inspired the immortal poem. The fort had undergone extensive repairs, and as the garrison flag, then in use, was old and too small, the soldiers and sailors of Baltimore desired a new one.

This was made by Mrs. Mary Pickersgill, assisted by her daughter and two nieces, at her home in Baltimore. The Flag was originally about forty feet long, but battle, time, and relic seekers have diminished it.

Each stripe measures nearly two feet in width, and the five-pointed stars are two feet from point to point. The Flag was made in sections, and because of its great length, it was found necessary to remove it to the loft of a neighboring brewery and set it in the canton with the stars.

The Flag was made in mid-August. A piece of red cotton cloth on the third white stripe from the bottom is supposed to represent the initials of Major Armistead, commander of the fort.

It was sewn on so hurriedly before the Flag went into action that the letter's crossbar was omitted. This Flag, among many others, has recently been preserved by Mrs. Amelia Fowler of Boston.

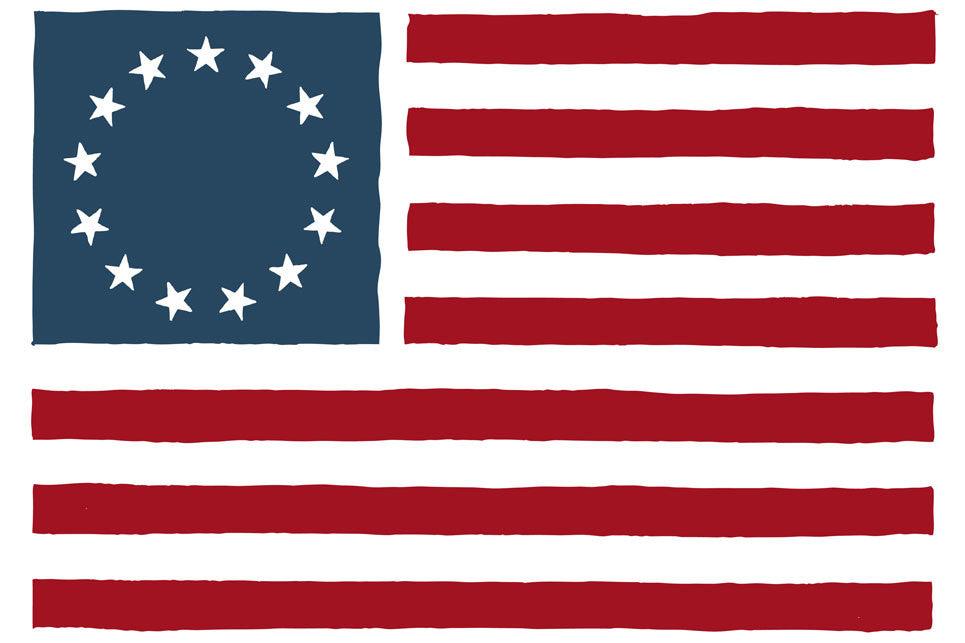

The images below are representative of the actual Star Spangled Banner flag that flew over Fort McHenry on that day and is now preserved in the Smithsonian Museum. You can notice the "tilt" in some stars, just as in the original Flag.

"Dawn's early light" The first stanza of the national anthem is projected prominently on the wall above the Star Spangled Banner flag.

Star Spangled Banner Flag Chamber

Where the original Star Spangled Banner flag went...

1814 - The battle occurred, and the Flag won its glory. Armistead was promoted to Lt. Colonel by Madison. Armistead died in service on April 25, 1818. He acquired the Flag sometime before that date, but at this point, it is unknown how.

1818—Armistead died, and " legend" says that the Flag was used at his funeral. However, in all the newspaper accounts of Armistead's funeral, there is no mention of the Flag being displayed. At his death, the Flag was passed to his widow, Louisa Armistead.

1824 - The Flag was used in a reception for General Lafayette.

1861 - Louisa Armistead died on October 3, 1861, and in her will left the Flag to her daughter, Georgiana Armistead Appleton. According to one of the Armistead family members, the Flag was sent to England for safekeeping during the Civil War, who made this statement in a newspaper interview in the 1880s. But Georgiana said, in a letter to Admiral George Preble, that the Flag was in her possession during the rebellion.

1873 - June 24, The Flag was displayed in the Charleston Naval Yards. Canvas backing was sewn on the Flag, and one of the first photographs was taken.

1876 - The Flag was loaned to the Navy Department for the Centennial Celebration.

1879 - Georgiana Armistead Appleton died in 1879 and left the Flag to her son, Eben Appleton.

1907 - Eben Appleton loaned the Flag to the Smithsonian.

1912 - Eben Appleton converts the flag loan into a Smithsonian gift.

1914—Amelia Fowler was commissioned to remove the canvas backing sewn on the Flag when it was photographed in 1873 and replace it with the present linen backing.

The 1818 Flag

Realizing that adding a new star and stripe for each new State was impractical, Congress passed the Flag Act of 1818, which returned the flag design to 13 stripes and specified 20 stars for the 20 states.

This Flag became the Official United States Flag on April 13, 1818.

Five stars were added for the admission of:

- Tennessee (the 16th State on June 1st, 1796)

- Ohio (the 17th State on March 1st, 1803)

- Louisiana (the 18th State on April 30th, 1812)

- Indiana (the 19th State on December 11th, 1816)

- Mississippi (the 20th State on December 10, 1817) was to last for just one year.

James Monroe was the only President to serve under this Flag (1817-1825).

Evolution of the United States Flag

No one knows with absolute certainty who designed the first stars and stripes or who made it. Congressman Francis Hopkinson seems most likely to have designed it, and few historians believe that Betsy Ross, a Philadelphia seamstress, made the first one.

Until the Executive Order of June 24, 1912, neither the order of the stars nor the flag proportions were prescribed.

Consequently, flags dating before this period sometimes show unusual arrangements of the stars and odd proportions, these features being left to the discretion of the flag maker.

In general, however, straight rows of stars and proportions similar to those later adopted officially were used.

The principal acts affecting the Flag of the United States are the following:

On June 14, 1777, to establish an official flag for the new nation, the Continental Congress passed the first Flag Act:

"Resolved, That the Flag of the United States be made of thirteen stripes, alternate red and white; that the union be thirteen stars, white in a blue field, representing a new Constellation."

Act of January 13, 1794 - provided for 15 stripes and 15 stars after May 1795, "known as the Star Spangled Banner Flag".

Act of April 4, 1818 - provided for 13 stripes and one star for each State, to be added to the Flag on the 4th of July following the admission of each new State, signed by President Monroe.

Executive Order of President Taft dated June 24, 1912 - established proportions of the Flag. It provided for the arrangement of the stars in six horizontal rows of eight each, with a single point of each star to be upward.

Executive Order of President Eisenhower dated January 3, 1959 - provided for the arrangement of the stars in seven rows of seven stars each, staggered horizontally and vertically.

Executive Order of President Eisenhower dated August 21, 1959 - provided for the arrangement of the stars in nine rows of stars staggered horizontally and eleven rows of stars staggered vertically.

Portrait of Francis Scott Key

Francis Scott Key, 1780-1843

Francis Scott Key was a respected young lawyer living in Georgetown, just west of where the modern-day Key Bridge crosses the Potomac River (the house was torn down after years of neglect in 1947).

He lived there from 1804 to around 1833 with his wife, Mary, and their six sons and five daughters. At the time, Georgetown was a thriving town of 5,000 people just a few miles from the Capitol, the White House, and the Federal buildings of Washington. But after war broke out in 1812 over Britain's attempts to regulate American shipping and other activities while Britain was at war with France, all was not tranquil in Georgetown.

The British had entered the Chesapeake Bay on August 19, 1814, and by the evening of August 24, the British had invaded and captured Washington. They set fire to the Capitol and the White House, the flames visible 40 miles away in Baltimore.

President James Madison, his wife Dolley, and his Cabinet had already fled to a safer location. Their haste to leave was such that they had to rip the Stuart portrait of George Washington from the walls without its frame!

A thunderstorm at dawn kept the fires from spreading. The next day, more buildings were burned, and a thunderstorm dampened the fires.

Having done their work, the British troops returned to their ships in and around the Chesapeake Bay. In the days following the attack on Washington, the American forces prepared for the assault on Baltimore (population 40,000) that they knew would come by both land and sea.

Word soon reached Francis Scott Key that the British had carried off an elderly and much-loved town physician of Upper Marlboro, Dr. William Beanes, and was being held on the British flagship TONNANT. The townsfolk feared that Dr. Beanes would be hanged.

They asked Francis Scott Key for his help, and he agreed and arranged for Col. John Skinner, an American agent for a prisoner exchange, to accompany him.

On the morning of September 3, he and Col. Skinner set sail from Baltimore aboard a sloop flying a flag of truce approved by President Madison. On the 7th, they found and boarded the TONNANT to confer with Gen. Ross and Adm. Alexander Cochrane.

At first, they refused to release Dr. Beanes. However, Key and Skinner produced a pouch of letters written by wounded British prisoners praising the care they were receiving from the Americans, among them Dr. Beanes.

The British officers relented but would not release the three Americans immediately because they had seen and heard too much of the preparations for the attack on Baltimore.

They were placed under guard, first aboard the HMS Surprise and then on the sloop, and forced to wait out the battle behind the British fleet.

Now let's go back to the summer of 1813 for a moment.

At the star-shaped Fort McHenry, the commander, Major George Armistead, asked for a big flag that "the British would have no trouble seeing it from a distance".

Fort McHenry, the place where Francis Scott Key observed that the "flag was still there" and wrote the words to "The Star-Spangled Banner" following an engagement with the invading British during the War of 1812, is located in Baltimore, Maryland.

Two officers, a Commodore and a General, were sent to Mary Young Pickersgill's Baltimore home, a "maker of colors," and commissioned the Flag.

Mary and her thirteen-year-old daughter, Caroline, worked in an upstairs front bedroom. They used 400 yards of best-quality wool bunting and cut 15 stars that measured two feet from point to point.

Eight red and seven white stripes were cut, each two feet wide. Lying out the material on the malt-house floor of Claggett's Brewery, a neighborhood establishment, the Flag was sewn together.

By August, it was finished. It measured 30 by 42 feet and cost $405.90. The Baltimore Flag House, a museum, now occupies her premises, which were restored in 1953.

The British bombardment began at 7 AM on September 13, 1814, and the Flag was ready to meet the enemy. The bombardment continued for 25 hours, with the British firing 1,500 bombshells that weighed as much as 220 pounds and carrying lighted fuses that would supposedly cause them to explode when they reached their target.

But they weren't very dependable and often blew up in mid-air. From special small boats, the British fired the new Congreve rockets, which traced wobbly arcs of red flame across the sky. The Americans had sunk 22 vessels, so a close approach by the British was not possible.

That evening, the cannonading stopped, but at about 1 AM on the 14th, the British fleet roared to life, lighting the rainy night sky with grotesque fireworks. Key, Col. Skinner, and Dr. Beanes watched the battle with apprehension.

They knew that as long as the shelling continued, Fort McHenry had not surrendered. But, long before daylight, there came a sudden and mysterious silence.

What the three Americans did not know was that the British land assault on Baltimore and naval attack had been abandoned.

Judging Baltimore as being too costly a prize, the British officers ordered a retreat.

Waiting in the predawn darkness, Key waited for the sight ending his anxiety: the joyous sight of Gen. Armistead's great Flag blowing in the breeze. When at last daylight came, the Flag was still there!

Being an amateur poet and uniquely inspired, Key began to write on the back of a letter he had in his pocket. Sailing back to Baltimore, he composed more lines, and in his lodgings at the Indian Queen Hotel, he finished the poem.

Judge J. H. Nicholson, his brother-in-law, took it to a printer, and copies were circulated in Baltimore under the title "Defence of Fort M'Henry".

Civil War envelope showing the American Flag with the second stanza from Francis Scott Key's poem, "Defence of Fort McHenry".

Civil War envelope showing the American flag with the second stanza from Francis Scott Key's poem, "Defence of Fort McHenry".

Two of these copies survive. It was first printed in a newspaper, the Baltimore Patriot, on September 20, 1814, and then in papers as far away as Georgia and New Hampshire. To the verses was added a note, "Tune: Anacreon in Heaven."

In October, a Baltimore actor sang Key's new song in a public performance and called it "The Star-Spangled Banner."

It was immediately popular and remained one of several patriotic airs until it was finally adopted as our national anthem on March 3, 1931. However, the actual words were not included in the legal documents.

Key had written several versions with slight variations, so discrepancies in the exact wording still occur.

The Flag Our beloved Star Spangled Banner flag went on view for the first time after flying over Fort McHenry on January 1, 1876, at the Old State House in Philadelphia for the nation's Centennial celebration.

The Star Spangled Banner flag now resides in the Smithsonian Museum of American History. An opaque curtain shields the now fragile Star Spangled Banner flag from light and dust. The Star Spangled Banner flag is exposed for viewing for a few moments once every hour during museum hours.

Francis Scott Key witnessed the last enemy fire on Fort McHenry, which was designed by a Frenchman named Jean Foncin and named for then-Secretary of War James McHenry.

Fort McHenry holds the unique designation of a national monument and historic shrine.

Since May 30, 1949, the Star Spangled Banner flag has flown continuously, by a Joint Resolution of Congress, over the monument marking the site of Francis Scott Key's birthplace, Terra Rubra Farm, Carroll County, Keymar, Maryland. Key wrote the copy for the Nicholson family in his hotel on September 14, 1814, for 93 years.

In 1907, it was sold to Henry Walters of Baltimore.

In 1934, the Walters Art Gallery, Baltimore, bought it at auction in New York from the Walters estate for $26,400.

In 1953, the Walters Gallery sold the manuscript to the Maryland Historical Society for the same price. Another copy that Key made is in the image below.

KEY, FRANCIS SCOTT. ORIGINAL MANUSCRIPT OF 'STAR-SPANGLED BANNER'

Additional facts on the history of the Fort McHenry Star Spangled Banner Flag.

Leave a comment